Medievalish 3.5

Word Games with George Herbert

Dear friend,

I hope that wherever you are, you are in the thick of spring. As for me, Denver has been either a sort of gray cold or harassed by an allergen-laden high wind for days. My spirit is just a bit shriveled up.1 When I feel this way, my mood is wont to darken all my projects. I lose interest in the podcast. I feel like I’m wallowing slowly through deep mud as I write. And of course, I fall prey to a lot of insecurities surrounding what I already have sent out in the world.2

I keep a note on my phone of links for moods like this one. In there, I rediscovered a wonderfully apt poem by George Herbert. It’s been a while since I relied on the “-ish” flexibility of Medievalish, anyway. Are you ready for a poem that initially looks like a charming word game and then lands a (gentle) punch?

First, a George Herbert refresher: Herbert was born in April of 1593 to aristocratic Welsh parents, as one of ten children. He went to Cambridge, sat in Parliament for a brief spell, and became a don at Trinity College. But he married Jane, his wife, and then decided to enter the Anglican priesthood. He became rector of the wonderfully named Fugglestone St. Peter as well as the close-by Bemerton. He wrote the divine collection of poems, The Temple, as well as prose exploring the call and shape of priesthood. But his works were all published posthumously, and he wrote in obscurity. Ill for much of his life, Herbert died at age 39 of consumption in 1633. He is buried at his parish in Bemerton.

Dive into George Herbert’s Paradise. You might want to read it slowly, a number of times, as the metaphor of the enclosed garden-orchard expands:

I Bless thee, Lord, because I GROW Among thy trees, which in a ROW To thee both fruit and order OW. What open force, or hidden CHARM Can blast my fruit, or bring me HARM, While the inclosure is thine ARM. Inclose me still for fear I START. Be to me rather sharp and TART, Then let me want thy hand and ART. When thou dost greater judgments SPARE, And with thy knife but prune and PARE, Ev’n fruitfull trees more fruitful ARE. Such sharpnes shows the sweetest FREND: Such cuttings rather heal then REND: And such beginnings touch their END.

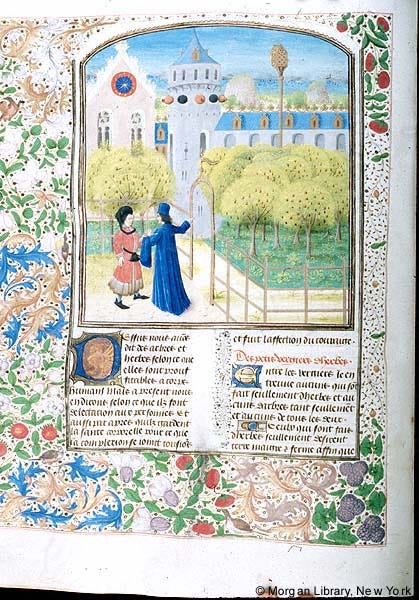

At first, one only notices the charm of the word game, Herbert’s evident joy in the play and pleasure of language. But then one begins to pay closer attention to the conceit of the enclosed orchard. In the first stanza, we see the initial picture: the orchard of fruit trees, in a row, the blessing to the Lord for our continued growth in this beautiful place.

The second stanza rejoices in the idea of enclosure, of being set apart. There is a peace here in the hidden garden, in its order and quiet ranks of trees. Orchards have long been known as places of contemplation and comfort. They evoke the magic and tenderness of the Song of Songs and its imagery of fruit and erotic love. Or they create hidden places of green in the packed streets of towns and cities like Early Modern London, or sheltered places in the country. No hidden deceit (CHARM) nor act of force (HARM) can ultimately destroy us in the protective arms of God.

Then, he requests that the Lord enclose us still—an initially startling request for many of us in modernity who associate freedom with roaming and big skies (I’m a Westerner, alright?). Yet this enclosure is not one of chains, but more like a swaddle, or the gentle holding of a mother—lest we START, as a baby wakes herself up with a gasp. Be to me sharp or TART, O God, begs Herbert.

This is the line that stops me for a quiet moment of contemplation. How bracing and refreshing to imagine the challenges of the life of faith as the tartness of fruit—a sourness that still has its pleasures, that awakens us into taste and life. This tartness is much preferable to the rottenness or dryness or lack of fruit that comes from an ignorant or negligent gardener, who keeps away their hands from the pruning and weeding and watering too, who has no sense of the ART of graced cutting. SPARE thy greater judgments, O God, prune and PARE me in your grace for better things, more beautiful flowers, a greater harvest of good and delicious glories.

At last, we recognize the truest FREND. We know that friend in the human sense: the treasured one who always combines truth and love together, the one whom we trust above all others. As this friend shows on Earth, so too is God the one whose truth mends while He RENDs, while he heals longterm through the short-lived bitterness of medicine and the pruning shears.

“And such beginnings touch their END,” concludes Herbert. This is not an end like the end of the story, but an end like a purpose—what we were made for. We prune early in the season, before the tree blooms and fruit forms, to create more fruit, more space, more health. You were made to bear fruit, to bring blessed tartness and tang and sweetness into the world, whatever form your fruit is (and the lovely thing is that our fruits are so various, so diverse, so different from one another). Peaches, nuts of every variety, cherries, avocados, quinces, pears, pomegranates, apples. A healthy fruit tree is one that has been cared for, watered, manured, and yes, pruned, cut back. Where, Herbert carefully asks, are you being pruned, and for what joys, what tastes and smells and beauty? Do not lose sight of the end hidden in the loss and the healing, he gently reminds.

By the way, all of this—the serious joy in play and image, the hidden conviction, the gentleness with a touch of steel behind—more deeply settles my conviction that George Herbert is somehow the Mister Rogers of the seventeenth century.

What I’ve been up to this month:

It’s my 36th birthday on Friday! 🎉 (you can give me a present by sharing Jesus through Medieval Eyes with someone 😉… or by having a really lovely date with a book of the past. Tag me on socials if you read something old and wonderful (or JtME) this week!)

Writing, writing, writing—and alongside, some solid sulking and agonizing.

I got to talk up my favorite, Julian of Norwich, on the C.S. Lewis podcast, Pints with Jack.

On Old Books with Grace, I have chatted with Laura M. Fabrycky on Dietrich Bonhoeffer, and coming up this week, with Lanta Davis on the formation of our souls when we practice “beholding” the writings and art of the past. Listen on Apple, Spotify, or the podcasting platform of your choice.

What I’ve been reading this month:

Nonfiction: I just purchased They Flew: A History of the Impossible by Carlos Eire… looking forward to starting!

Fiction: My first ever Graham Greene novel, The Power and the Glory.

Medieval/Medieval-adjacent: When am I not reading Piers Plowman? Always the C-text, naturally, but this month, it’s been Langland’s famous confession of the Sins in passus VI.

Article: A couple in Lincoln found a medieval artifact hidden in their bathroom.

A Prayer from the Past

Today’s prayer is from The Penitent Pilgrim (published in London, 1641)… as far as I can tell, this book was most likely written by Richard Brathwait (1588-1673), an illustrious gentleman who also wrote the hilariously titled Drunken Barnaby’s Four Journeys.3 He was also the first known person to use the word “computer.” Some of the online sources attribute The Penitent Pilgrim instead to Henry Herdson, who wrote on memory. I first discovered The Penitent Pilgrim, though not this particular prayer, in my darling tiny purple book of prayers from 1928, Prayers Ancient and Modern, compiled by Mary Tileston.

Look upon me, dear Father…

Whence I perceived, by the influence of thy sweet Spirit, whereby I became enlightned, that whensoever I fell, it was through my owne frailty; but whēsoever I rose, it was through thy great mercy. Yea, I found thee ready in every opportunity, to afford me thy helping hand in my greatest necessity. When I wandred, thou recalled me: when I was ignorant, thou instructed me: when I sinned, thou corrected mee: when I sorrowed, thou comforted me: when I fell, thou raised me: when I stood, thou supported mee: when I went, thou directed me: when I slept, thou kept me: when I cried, thou heard me.

Nay, shall I more fully declare thy goodnesse towards me? If, after these few but evill dayes of my pilgrimage; even now, when the keepers of the house tremble, and the strongmen bow themselves, and the grinders cease because they are few, and they waxe darke that looke out by the windowes; if I say, after these many, too many misspent dayes, I abuse thy gracious patience no more with fruitlesse delaies, but with my whole heart repent me for offending thee, thou forthwith sparest me: if I returne, thou receivest me. …Thus doth thy mercy reclaime me straying, invite me withstanding, expect me foreslowing, embrace me returning. …

Amen.

Peace for your May,

Grace

P.S. Medievalish is free, and I’d be delighted if you shared it with a friend!

If you have enjoyed this newsletter, you may also like upgrading to a paid subscription to receive other essays scattered throughout the month on medieval and early modern books and thinkers. Plus, you directly support my writing and podcast projects! In the last month for paid subscribers, I’ve written about a wonderful poem on the sacrament of baptism called Saint Erkenwald, the York Cycle of mystery plays, and a fourteenth-century book meant for teaching lay folk the basics of the faith…

It doesn’t help that the Phoenix Suns, my only true loyalty in the world of professional sports, were humiliatingly swept in the first round of the playoffs.

Don’t cringe over or even look at the Goodreads reviews, Grace. Stop checking the sales on Amazon or googling yourself like a fool. Just keep writing and keep listening to the Dune 2 soundtrack.

Please, someone out there write a delightful picaresque novel with this title. You’re all a bunch of writers, I know we can make this happen!

Thank you for this lovely walk through George’s garden this morning. I look forward to exploring his work, despite his publisher’s’ unfortunate subtitling. 😅

I also look forward to listening to the podcast, which I didn’t know about until now-and I’m ALWAYS up for a good Lewis discussion, so thanks for that!

I think I'm going to be sitting and praying with that poem for a long time. Truly something to savor.