Dear friend,

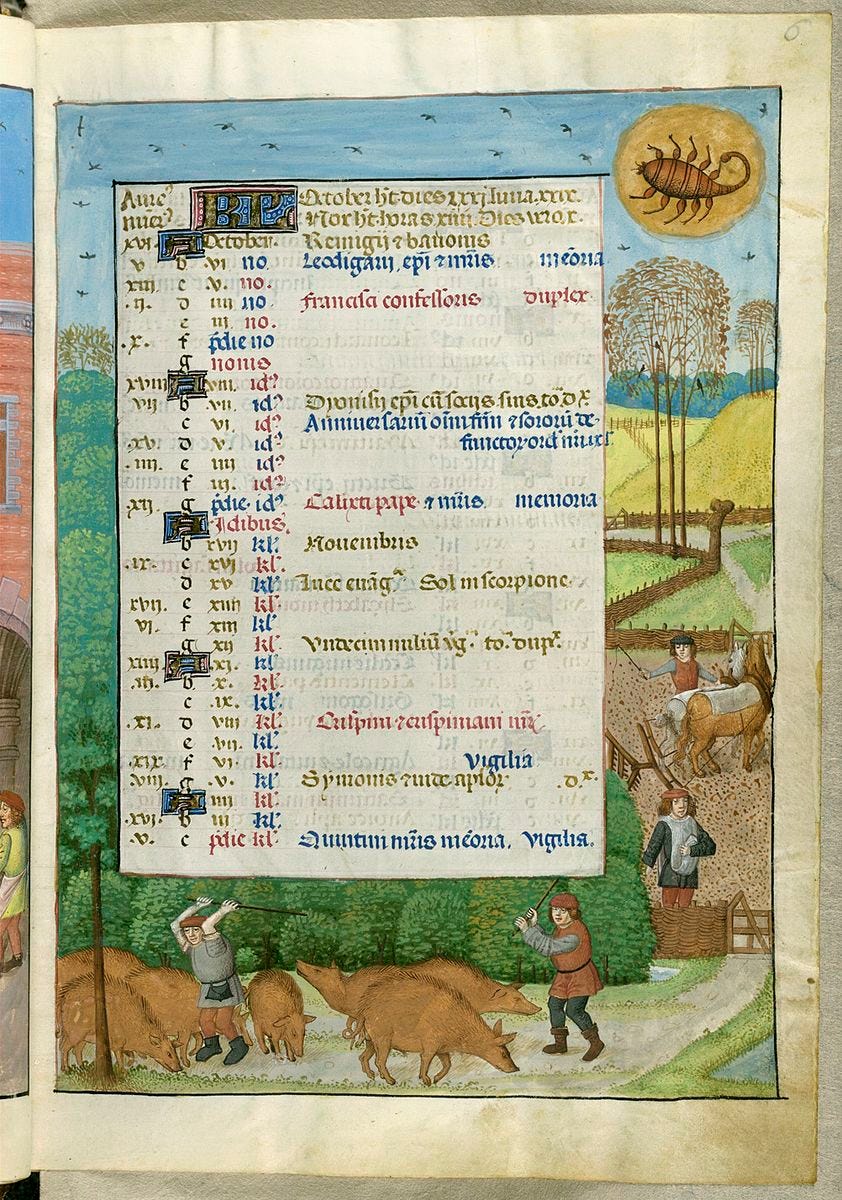

Ready for a cheery October newsletter on remembering that you will, someday, fade and perish? I’m ready to listen to all the Halloween skeletons.

I have reached an age (a dignified thirty-five years old) where, for the first time, I have begun to look at my peers and notice, to my surprise, that they look old. I probably look old too. There is a certain humor there—I know we are not that old—but it’s funny to notice for the first time on your peers wrinkles, gray hairs, skin and bodies all more deferential to the demands of gravity than before.

It is also, naturally, fall.1 A couple of weeks ago, I wrote a post for paid subscribers on Michaelmas, the feast of St. Michael the Archangel and all angels, that started me thinking about my melancholy feelings this time of year. I dread winter. This former desert rat dreads cold weather so much that sometimes it’s hard for me to appreciate the loveliness of fall except as a harbinger of ice and snow.

But lately I’ve been thinking of the graciousness of the Maker. I suspect that one of the many reasons the Maker has crafted these seasons is to give us time and space to reflect on birth and death, beginnings and ends and resurrections, through the beauty of the created world. We have been given a natural, kind memento mori, a beautiful season of endings, to recollect our own ends in the gently insistent fire of the leaves, and dying flowers, and darker, longer nights. There’s a grief there that would be folly to ignore or gloss over. And there is beauty and promise that also requires attention.

I haven’t really come across many Middle English poems about changing leaves (please tell me in the comments if you have, I certainly have not done an exhaustive search) but there are many poems about the necessity of remembering your own death, and even some about remembering death in the context of fall:

Nou skrynketh rose & lylie flour that whilen her that suite sauour in somer that suete tyde; ne is no quene so stark ne stour, ne no leuedy so bryht in bour that in ded ne shal by-glyde. whose wol fleysh lust forgon & heuene blis abyde, on ihesu be is thoht anon, that therled was ys side... Now withers rose and lily flower that once gave out sweet scent in summer, that sweet season; There is no queen so mighty & powerful, Nor any lady bright in bower that will not smoothly pass into death. Whoever wills to forgo desire in their flesh, and abide in heaven's bliss, Let his thought be on Jesus, whose side was pierced. (translation mine, original from MS. Harley 2253, ca. 1350)

There are more stanzas of this serious little poem, but note how it ends:

falewen shule thi floures.

Iesu, haue merci of vs,

that al this world honoures. Amen.

Your flowers shall fall,

Jesus, have mercy on us,

you whom all this world honors. Amen.All the flowers fade, but Christ has mercy and will have mercy, and holds it all in his hand. Resurrection awaits.

Some of these memento mori poems are very bleak as they knowingly stir up the intense dread of the pains of hell to get the listener to amend their behavior. But some are more subtle, more thoughtful about the place of death within the promise of resurrection. Most have both aspects.

An otherwise longish and fairly unappealing later Middle English poem, from the fifteenth century, calls death “the Soul’s friend” (a phrase which reminds me of Emily Dickinson) and one very lovely set of verses. I can think of it more that way as I consider the beauty of autumn. It urges us:

Thynk, man, inwardly on this,

& be thou noght vn-kynde;

Thynk & forget noght that blys,

that made es ffor man-kynde...

Think, man, inwardly on this [your death],

and do not be unnatural,

Think and do not forget that bliss

that mankind was made for... (Cambridge University MS. Gg. I. 32)You might remember, from previous work I’ve done, my obsession with the Middle English word kynde… it’s quite theologically beefy. An ancestor of our modern word “kind,” kynde means natural and/or kind, deeply appropriate and befitting, or a type of something.

Is this poem saying that death is natural? This seems wrong—death and loss feel so jarringly wrong, so clearly part of a wounded world. This is where kynde gives us room to breathe in our thoughts of mortality. Death is kynde in one sense, that we have mortal bodies and that all die. Death is also unkynde for us as people created to love into eternity. By our kynde, we belong to the bliss of Christ.

It is more accurate to say that the poem insists it is unnatural to not think of our own ends, to live as if we are undying. Memento mori is kynde, befitting to us as embodied creatures in God’s image. Memento mori reminds us, at times even humorously, of who we are: our acts, even the most impressive ones, are impermanent. Our hobbies, even the most delightful, are not the point but surprise, gift on gift on gift. Our failures, pettinesses, and cruelties also thankfully have an end.

It is not only unnatural but unkind to ourselves to live as if we were not going to die. We forget who we are and run into all kinds of problems when we are unmoored from the recollection of our proper ends.2 Remembering that I will die paradoxically opens up a particular, kynde part of being human in the practice of truthful humility and joy in what we have been given. We receive the breathtaking, fleeting joy and real melancholy in autumn leaves. For we recognize our very real death is not our truest end, just as fall and even the deadest of winter are never the last word on life.

On that note, a premature blessed Feast of All Souls to you, dear reader!

What I’ve been up to this month:

Jesus through Medieval Eyes comes out on Halloween (!!!!). I got the hardcopy this week and it is so beautiful; I’m incredibly pleased with how it turned out. The gold foil (so medieval!) and colors of the art insert catapulted me into joy. You can preorder the book anywhere you get books, including Amazon, B&N, and your local bookstore.

The Old Books with Grace podcast has had a good month: this week, I welcomed

on imagination and culture; two weeks ago I spoke with Marianne Wright of on the great Victorian novelist George MacDonald. Listen on Apple, Spotify, or the podcasting platform of your choice.Working on some other secret (for now) projects that I look forward to sharing with you!

What I’ve been reading this month:

Fiction: I’ve been reading Maud Hart Lovelace’s Betsy-Tacy books where Betsy is in high school. Old-fashioned and lighthearted.

Nonfiction: Hans Urs von Balthasar, Unless You Become Like this Child. Taking it very slow.

Medieval/medieval-adjacent: 14th & 15th century Middle English lyric poetry. Gems galore.

Article: I enjoyed this piece in Comment from Matthew Milliner on goddesses and Mary.

A Prayer from the Past

In light of the terrible violence in the Holy Land, the oppression of people all over the world, and the cruelty and opportunism of war in Ukraine and other places, I invite you to pray the familiar and well-loved words of St. Francis of Assisi (d. 1226) this month. It was also his feast day last week.

Lord, make me an instrument of Your peace; Where there is hated, let me sow love; Where there is injury, pardon; Where there is discord, harmony; Where there is error, truth; Where there is doubt, faith; Where there is despair, hope; Where there is darkness, light; And where there is sadness, joy. O Divine Master, Grant that I may not so much seek To be consoled as to console; To be understood as to understand; To be loved as to love. For it is in giving that we receive; It is in pardoning that we are pardoned; And it is in dying that we are born into eternal life. Amen.

Peace for your October,

Grace

P.S. Medievalish is free, and I’d be delighted if you shared it with a friend!

If you have enjoyed this newsletter, you may also like upgrading to a paid subscription to receive other essays scattered throughout the month on medieval and early modern books and thinkers. Plus, you directly support my writing and podcast projects! In the last month for paid subscribers, I’ve written about a lovely and mysterious fourteenth-century Middle English poem, a sermon on the feast of St. Michael and All Angels, and an introduction to a lesser known medieval theologian, William of Auvergne…

Time for my bonus word origin rant (on a totally different note) about fall vs. autumn. There are a ton of memes out there that make fun of Americans for saying fall instead of autumn like the British, like it’s a failure of intelligence. But everyone used to use fall for this season! It’s not new. It’s not even American. Harvest is older than both as an English word for this season, if you want to be the most traditional. And fall is a lovely linguistic parallel to SPRING, when plants spring forth from the ground, and leaves spring from dead branches. So use whatever word you want for this season. End rant.

Tolkien is the master of showing the sadness and necessity of this in the elves of Middle Earth, who despite their immortality are the masters of memento mori. Because of their past attempts to hold tightly to fleeting things in their own undying natures, they have now learned, and hold a proper sadness and joy that are two sides of the same coin in the beauty of their fleeting life in Middle Earth.

Been spending a lot of time in the old cemeteries around town this fall. This all feels very appropriate. I'll be praying with it for the rest of the month

Oh Grace, this is just beautiful - I think we so often treat our mortality in that unkynde way. Your closing prayer reminds me, too, of St. Francis' mention of Sister Bodily Death! Ah, to call death 'sister' - what a remarkable peace.

I can think of Old English poetry about falling leaves, but not Middle! I'm intrigued!

Also - your book comes out on Halloween?! Even more perfect! The cover with the gold foil and all those shifty Medieval eyes is just the best.