Dear friend,

I have been thinking about fear lately. I’ve always liked Halloween, but more for the neighborly spirit, kids in costume, and pumpkins. I’m not the chainsaw, haunted house type. Spooky and enchanted is more fun than terrifying. But the main appeal of the modern secular holiday (not counting All Hallows’ Day or All Souls’ Day ) is that it offers domesticized, invited fear: pleasant butterflies or terrified shrieking, but under controlled conditions. I include even the small level of fear that costumes invite in becoming something other than yourself. My son as a toddler refused to dress up because he would always, with a slight tinge of worry, insist he was Simon. There’s certainly an element of risk behind costumes, a blending of yourself into something strange, otherworldly, daring.

Then, there are other kinds of fear—anxiety, panic, many more. Obviously, the really bad kind that we all instinctively feel, triggered by an unexpected call from a loved one at midnight. And then, strangely, spiritual fear.

There’s a category of medieval writing called penitential manuals. These were manuals in our modern sense, like a car manual, but for priests learning pastoral care and guiding their parishioners through the sacrament of penance, including confession. Many of these were also read by lay folk wishing to confess more fully and faithfully in their spiritual journey. These books often consisted of explanations of the Lord’s Prayer and the Apostles’ Creed, the seven sacraments of the medieval church, and lengthy descriptions of the seven capital vices by which all of us are tempted. Some of them also included the “remedies” to these vices, virtues which provided counterpoints to those vices. Many added to these virtues “gifts of the Holy Spirit,” and understood them to provide a path of spiritual wisdom and growth in our lifelong struggle against vicious and selfish living—sanctification after the ongoing grace of baptism. The Book of Vices and Virtues, a fourteenth-century English translation of the Somme le Roi, describes how the “Holy Gost” teaches “oure hertes” with gifts and in the process "doeth away and destroieth” the seven deadly sins.

The first gift of these graces of the Holy Spirit is fear. Fear as a gift? The anonymous writer argues that when we are sinful, we live in intoxicated disregard to ourselves—like a drunkard passed out naked in a gutter outside a tavern, he writes, we are insensible to our sad, lonely, and dangerous state. The Holy Spirit “visiteth” us and “waketh” us from stupor, giving back to us ourselves, us our wits, our memory, and bringing us again to him, so that “he [the man] beginneth to know hymself and reckoneth what goods he hath lost and in what desperation he has fallen through his sin…”

This awakening, a coming-back-to-oneself, takes the form of fear. What have I lost? What am I losing? The writer cites the questions that the angel asked Hagar in Genesis: “Where are you coming from? Whither are you going? What are you doing?” The penitential writer then goes a little more hardcore, saying, “Wretch, behold yourself!” When one seriously beholds oneself in sin, it is frightening to see what one has become.

At this point, you might be about ready to exit the email, muttering to yourself that you didn’t really need a seven-hundred year-old penitential manual telling you you’re a wretch today. I promise there’s value to be extracted here, despite this rhetoric that can obscure the heart of the idea for us. This particular manual is actually pretty tame compared to many of them, who really relish the whole wretch and damnation stuff (you’re a vas stercorum, literally “bag of shit,” in many of these kinds of texts, or a “barrel of dung” in a memorable phrase by John Donne).

Dung aside, the gift of this fear is paradoxically a recognition of worth—your own worth. It’s a coming back to yourself, a recognition of dignity and identity: I do not belong in a gutter. I am adored, created, and celebrated by the Creator. Healthy fear in appropriate situations is a gift for humans. I am not talking about anxiety or terror, but the fear naturally caused by steep cliffs, big waves, animals stronger than ourselves, and the super scary necks of newborns (careful! careful! as I watched my toddler gleefully hold the newborn). Our fear nudges us to recognize the value of our fragile, small lives and take care of ourselves. (This is also why recklessness is not a virtue equivalent to courage.)

The writer states it plainly: this holy fear blossoms into humility. As Geoffrey Chaucer translated that same century, humility is when a person holds “verray [true] knowleche” of oneself. Spiritual fear is not an end point, but an invitation to another life and deeper knowledge of who we are, who God is, and where we are going. Thus fear becomes a recognition of littleness, an embrace of need and acknowledgement of desire for wholeness, holiness, health, and healing, all of which come from the same root word in the depths of time. I am limited, beautiful, created, error-ridden, even rotten at times, and always cherished. I need help, lots of it.

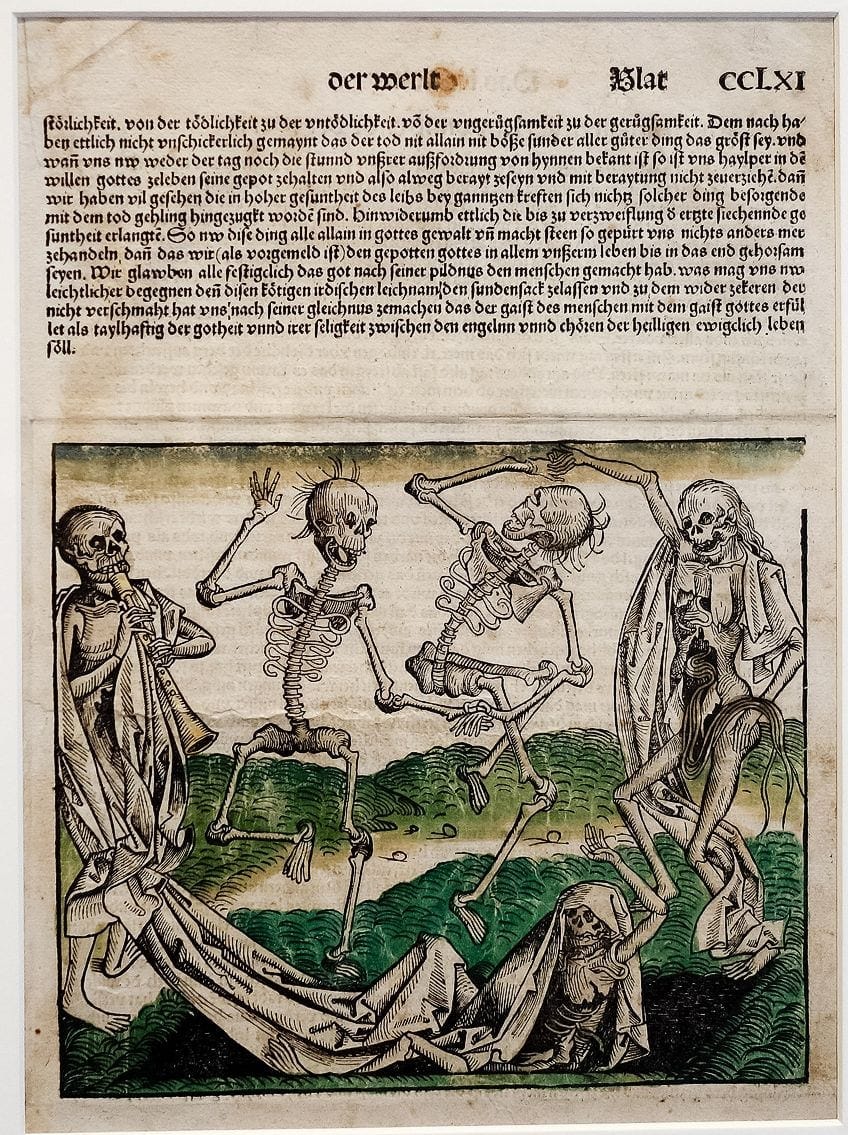

This recognition of the role of spiritual fear is partially why medieval people were so interested in the idea of memento mori. Remember your death, remember that you are dying. You are a marvelous creation resonant with the music of eternity and a miraculous bag of bones (and excrement!) on a rock in space. Hold the tension as you remember again the tricky, wondrous mess of complication that entails being an embodied image of God. Graciously, the labor of soul-searching gives birth to peace.

Though our modern Halloween did not really exist in medieval times, I think it can give us some of these medieval gifts of remembrance. I’m not talking about the gore or terror, but about the cheery, spooky skeletons and ghosts, the glowing pumpkin in the dark night, the thrilling risk of costumes. If we accept the invitation, the reminder of fear as a potential gift offers us a chance to ruminate, to fearfully and wonderfully recall who we are, the fleeting beauty of life on Earth, the gift of breath and being together, even the incarnational weirdness that God had a skeleton too. Very few holidays utilize the emblems of embodiedness so jubilantly.

There is another kind of spiritual fear that these writers considered that is closely related—fear of God… the newsletter ultimately got too long to cover it all…

What I’ve been up to this month:

An essay of mine on hope came out in the newest Fathom Magazine. Read for my thoughts on hope as the virtue of pursuit, cousin to courage (and for some Gerard Manley Hopkins).

The Old Books with Grace podcast is going strong: this week, I welcome Gina Dalfonzo on Charles Dickens; two weeks ago I spoke with Oxford lecturer Eleanor Parker on the delights of Old English. Listen on Apple, Spotify, or the podcasting platform of your choice.

The Medievalish Book Club is beginning! If you upgrade your free membership to a $10/month subscription, you receive access to a book club, led by me, focusing on medieval and early modern literature with occasional forays into later stuff. You can read more about it here.

What I’ve been reading this month:

Fiction: More Anthony Trollope. I’ve been slowly rereading his two big series, picking them up in odd moments between Big Books and Medieval Things. Lately it’s been The Eustace Diamonds, which is really very funny (although I always get stressed reading about chronic liars, as I cringingly anticipate the collapse of their houses of cards).

Nonfiction: Friends, I forgot that libraries include cook books. I have checked out two of them, including one on soups (!). It’s a literally hot fall tip, in case anyone is stuck in a cooking rut.

Medieval/medieval-adjacent: Combing through fourteenth- and fifteenth-century short poems for the Advent series. So much beauty, but I still haven’t found quite what I’m looking for.

Article: What do Jedi knights have in common with medieval monks? This article from Plough reminded me of my uncle who passed away last December, who loved Star Wars. It’s also nice to remember when you see all the little Darth Vaders and Luke Skywalkers at your door in a couple of weeks.

A Prayer from the Past

This prayer, with its mist rising from the hills and soul, evokes crisp fall dawns. I am praying these old words as I rise in the dark to wake my children and dress in the warmer clothes that Colorado autumn requires.

This is from a collection of prayers, poems, and rituals from the Scottish Highlands that Alexander Carmichael collected and published in the nineteenth century, Carmina Gadelica.

Thanks to you, O God, that I have risen today, to the rising of life itself; may it be to your own glory, O God of every gift, and to the glory of my soul likewise. O great God, aid my soul with the aiding of your own mercy; even as I clothe my body with wool, cover my soul with the shadow of your wing. Help me to avoid every sin, and the source of every sin to forsake; and as the mist scatters on the crest of the hills, may each ill haze clear from my soul, O God.

-Anonymous, adapted from the Carmina Gadelica

Peace for your October,

Grace

Oh Grace, I love all of this - so, so much. The Church continues to be my school of paradox...where we ourselves are walking paradoxes, aren't we? Beloved images of God, yet also bags of bones. I feel like our modern culture tries to shy away from anything vaguely reminiscent of memento mori, and there's a big loss in that. Thank goodness for the Medievals! How beautiful and inspiring to see fear as a grace. I think of St. Francis calling Death by the title of Sister...

(Also, it really doesn't get better than vintage Halloween greeting cards.)

always been a huge fan of memento mori, wretch that I am...