Dear friend,

The prophet Isaiah writes, in some of the most beautiful prophecies of the coming Messiah, that

A shoot shall come out from the stump of Jesse,

and a branch shall grow out of his roots.

The spirit of the Lord shall rest on him,

the spirit of wisdom and understanding,

the spirit of counsel and might,

the spirit of knowledge and the fear of the Lord.

His delight shall be in the fear of the Lord.

He shall not judge by what his eyes see

or decide by what his ears hear,

but with righteousness he shall judge for the poor

and decide with equity for the oppressed…

The wolf shall live with the lamb;

the leopard shall lie down with the kid;

the calf and the lion will feed together,

and a little child shall lead them…

Isaiah 11:1-6 (NRSV)

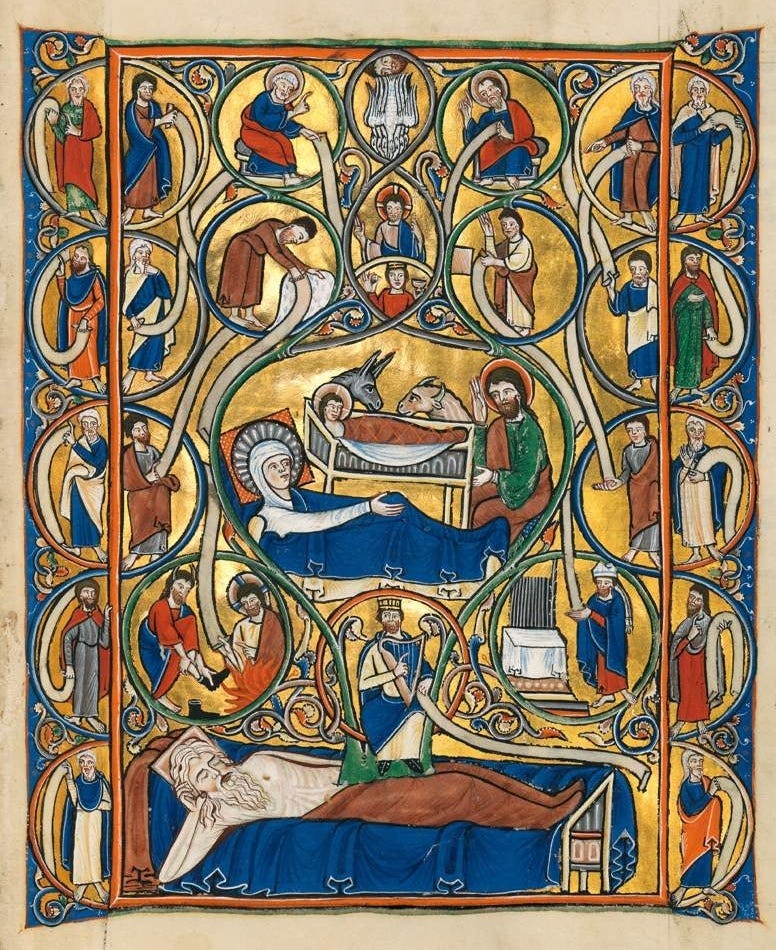

Medieval artists loved the idea of the shoot emerging from the stump of Jesse. In stained glass, on cathedral facades, carefully inscribed books of Psalms and prayers, they fashioned their own representations of this idea, called the Tree of Jesse.

Take a closer look at this one, from a Book of Psalms. In each corner, a symbol of each of the four gospel-writers offers truth and witness to Christ. In the middle of the page, Jesse, the ancient Hebrew patriarch and father of King David, slumbers. Out of his body near his heart grows a great vine. This vine flowers with the prophets and kings of God’s covenant with the Jewish people. But at the top of the vine blooms the largest and most beautiful blossom of all, gold-leafed and glorious: Mary and her Son.

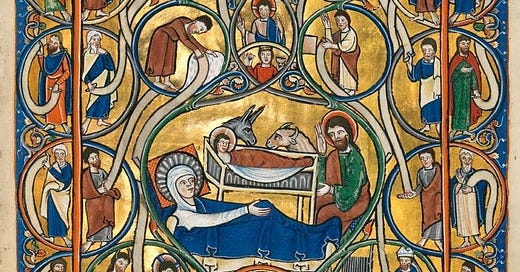

Here’s another manuscript illustration that’s a little more provocative:

I love this one partially because Mary is resting after giving birth to Jesus while Joseph watches the new baby, and the animals eye each other with delight and affection in the glow of the newborn God. But the main thing I love about this representation is noticing where the Jesse Tree emerges: Jesse’s groin!1 From post-birth authenticity to reproduction, the artist does not want you to miss the very material, embodied relationship of Jesus to his family and people. That medieval earthiness emphasizes what we already see here: this is the Savior’s family tree, made up of real people with real bodies, flaws, and stories. Fascinatingly, the medieval Tree of Jesse is the original use of a tree to depict the genealogy of a family. And Christ’s real human family helps us to see the full picture of the good news. Why?

When my oldest was born, I recognized her hands immediately. They belonged to my husband’s side of the family. They were her own tiny, swollen, reddened newborn hands, yet they belonged to a larger history of love and faithfulness and generation. The earlier molds of these hands had baked bread, pulled weeds, wrought beautiful and terrible works. The Son did not only take on flesh, he took on David’s sometimes troublesome courage and cowlicks, Anne’s devotion and double-jointed pinky fingers. He comes from a line of real and complex people: faithless and faithful, abusers and abused, holy and broken. Baby Jesus is born into our funny human particularities and our burdensome histories, into created time and place.

In his recent book, How to Inhabit Time, James K.A. Smith reminds us that “at the heart of Christianity is not a teaching or a message or even a doctrine but an event.” Smith tells us that when Jesus promises that he will never leave us or forsake us, his words are “a promise of presence through history—not above it or in spite of it.” We can even be more specific—it’s not abstract human history, but through the particularity of a human family, not beyond or in spite of it.

Medieval theologians like Thomas Aquinas surprise us, perhaps, when they note that God’s salvific work did not have to happen the way it did. God could have chosen another path than Incarnation. Or at least, he could have done Incarnation more tidily, magically spoken himself into flesh at a safe remove from the complicated inheritances of a human family. Zeus did so in Greek myth countless times. If the Ancient Greeks could imagine it, it certainly could have been so. Instead, he joins us in our complex web of generation, adoption, relationship, and dependence in the Jesse Tree. We belong to Him. Equally and shockingly, God belongs to us. Christ is a shoot from a human family. He needs his mother, receives affection from his grandparents, deals with uncomfortable family history at holidays, and carries the unseen bodily inheritance of generations. He is truly God-with-us, Emmanuel.

All the more meaningful, then, that Christ chooses dependence, messy human relationships, and bodies to fulfill the prophecy of Isaiah 11, the peaceable kingdom. All of us living in our own family trees recognize the miracle at the heart of redeeming the universe from within the particular brokenness and beauty of a family. The blooms on the illuminated page, with a tiny prophet or king contained within, support and grow towards the large flower of Mary and Jesus. Because Christ is now kin, we call to him with confidence. He’s our family now.

Both families and shoots are a process, which offers insight into another tree of Jesse moment, in the great Advent hymn O Come O Come Emmanuel. One verse calls to the Rod of Jesse:

O come, Thou Rod of Jesse, free Thine own from Satan’s tyranny; From depths of hell Thy people save, And give them victory o’er the grave. Rejoice! Rejoice! Emmanuel Shall come to thee, O Israel.

I always wondered about the connection between the “Rod of Jesse” and freeing the captives. While singing this verse, I used to picture the Rod of Jesse giving devils a good, hard smack to release the captives. But of course, rod actually translates this root/branch/shoot idea.

I now envision patient growth from within the family tree, the strength of kinship and love, latent power that emerges and surprises over time. Similar to Christ’s tale of mustard-seed faith, the Rod of Jesse is that shoot that begins in between a sidewalk crack and eventually breaks apart the stifling, tyrannical concrete that would keep it from its full and ancient strength reaching towards heaven. Free thine own, Christ. As the little twigs and leaves grafted into the vine of Jesus (John 15), we are participants in the concrete-busting peaceable kingdom of the shoot of Jesse.

What I’ve been up to this month:

I was a guest on Charity Hill’s Bright Wings podcast, to discuss the Middle Ages and the mythologies we build around it. Check it out on the podcasting platform of your choice, including Apple and Spotify.

Recent Old Books with Grace podcast episodes: Don’t miss out on the Advent series. Each episode focuses on a different poem (or set of poems) that is Advent- or Christmas-adjacent. So far, I’ve done an episode on T.S. Eliot’s The Journey of the Magi and George Herbert’s The Bag. I hope you are enjoying this series as much as I enjoyed writing it—a tall order, because I love Advent and writing about Advent! Catch the series wherever you listen to podcasts, including Apple and Spotify.

Revising, revising, revising… 👀

What I’ve been reading this month:

Fiction: Don’t mind me, just crying while I read the children’s classic chapter book Betsy-Tacy by Maud Hart Lovelace with my oldest. 😭

Nonfiction: I cannot wait to dive into Denys Turner’s new book on Dante.

Article: Caitrin Keiper’s beautiful reflection on Advent & birth in Comment.

Medieval/medieval-adjacent: Continuing to read Julian of Norwich with the Medievalish Book Club. Delight. Read with me?

A Prayer from the Past

This poem-prayer was written by the English poet and Jesuit priest, Gerard Manley Hopkins (1844-1889), one of my favorite poets. I found it in Elizabeth Goudge’s wonderful collection of prayers, A Diary of Prayer.

Moonless darkness stands between. Past, O Past, no more be seen! But the Bethlehem star may lead me To the sight of Him who freed me From the self that I have been. Make me pure, Lord: Thou art holy; Make me meek, Lord: Thou wert lowly; Now beginning, and always: Now begin on Christmas day.

Amen.

Peace for your December,

Grace

P.S. As always, this newsletter is free, and I’d be delighted if you shared it with a friend!

Jesus is adopted by Joseph into the house of David. But in classic medieval fashion of elaborating in not-always-scriptural modes, medieval theologians usually followed a tradition of believing Mary to be a distant cousin of Joseph, a descendant of David via a different line.

As an adoptive mom, I also have come to deeply appreciate Jesus’s connection to the royal line of David through his adoptive father Joseph. So while I certainly want to honor the physical/biological connections Jesus had with his ancestors, it’s also very important to me to remember that he’s in the royal line of David through Joseph, and that the connection to his ancestors is not *only* biological. ❤️