Dear friend,

Alas, I wrote an entire fresh letter for you, only to realize I had unwittingly rather closely rewritten a section of my forthcoming book and had to delete it all. I don’t want to spoil the surprise. This is a risk you take in reading me. I am deeply, deeply obsessed with some particular things that tend to come up again and again.

So I switched gears and rewrote a paywalled post from over a year ago to share with you all! I don’t share too many more personally-themed essays on Medievalish—I know most of you are here for my little dives into medieval Christianity and literature, and not my enthralling personal backstory. But “How did you get into this?” with the this meaning the strange and obscure world of premodern English poetry and contemplative writing, is one of the questions people most frequently ask me. I had to answer it twice last week alone. I thought it might be fun to share a little of that story with you.

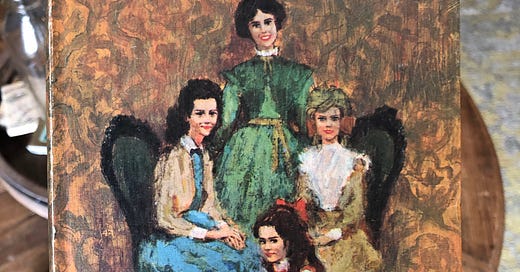

I’ve always loved history and literature. The summer after third grade, my family was visiting Julian, California on a dusty, sunny day. We all had pieces of apple pie and then we walked over to a used bookstore. I distinctly remember walking and blinking within the dark interior, smelling that distinctive old book smell. And I found what I had wanted for that whole year, ever since a librarian had told me I was too young to understand it: a copy of Louisa May Alcott’s Little Women. I devoured my slightly battered and rather ugly 70s copy in the car on the way home, growing more and more carsick in the twisty turns on the backroads of Southern California. Little Women fed something deep in me. It was not the words or story alone that I loved, though I loved those, but the world of the past, the different ways of seeing and being.

At university, I begrudgingly became a psychology major with no clue of what to do, because it seemed more “practical” than being an English major. When people asked me what I loved as they tried to help me figure out what I should do with my life, I always answered with confusion and a little bit of embarrassment: “Books.” I didn’t even want to be a writer or teacher at that time, just “books.”

But it was not long before it became clear even to me, an occasionally obtuse individual, that I was not cut out to be a school counselor or therapist (huge shout out here to our good folks helping with mental health!). I decided to throw my pretenses at practicality overboard. I embraced my aimless bookishness. I had already taken so many psych classes that I double majored in it alongside English. Then, for the first time, I encountered Middle English.

I took a course called the History of the English Language. The professor was a dour, terrifying, ancient man whose tests were all based on footnotes. And yet, I fell in love with older forms of English and all its tricks. Here’s something about me: I am a fun fact queen. I was in heaven. I learned so many English fun facts, with which I entertained (tormented?) my family and boyfriend. Have you ever wondered why we say pork and mutton instead of pig and sheep? The original English words, pig and sheep, were retained by the lower classes, the speakers of Old English, raising the animals. Yet the meat, the end result of their labors, was eaten by the Norman French conquerors of the upper class—whose names for pig and sheep were mouton and porc! The animals retained their lower class, different language names, while the food consumed by the rulers now had new names. English is the best kind of puzzle, filled with class differences and history and slang and metaphor.

Deeply intrigued, I took a class on Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales. It was interesting, but did not capture my heart—which still belonged to Victorian novels like Little Women and a newfound favorite, the writer Anthony Trollope.1 Then I finished college, drawn to graduate school but uncertain whether it was right for me. I decided to go for it once I realized I could do it with a scholarship, thinking I would study novels. I was wrong.

My very first class of graduate school was a Middle English poetry class of authors other than Chaucer. The very first poem we read was Sir Gawain and the Green Knight. This poem enchanted me in the way that Gerard Manley Hopkins and T.S. Eliot had only scant years before, when I had first realized that poetry was not inferior to the novel. Lines like this mesmerized me. I am only going to give it to you in the Middle English first, so that you focus on the sounds and feel alone without worrying about meaning. The funny squiggly line is called a yogh, and it is pronounced like a guttural y or sometimes a g.

Now neȝes the Nw Ȝere and the nyȝt passez, The day dryuez to the dark, as Dryȝtyn biddez. Bot wylde wyderez of the worlde wakned theroute; Clowdes kesten kenly the colde to the erthe, Wyth nyȝe innoghe of the north the naked to tene. The snawe snittered ful snart, that snayped the wilde; The werbelande wynde wapped fro the hyȝe And drof vche dale ful of dryftes ful grete. (lines 1998-2005)

Make an attempt to read it aloud if you’re in a space where no one is listening and you can’t embarrass yourself!

All of Gawain still dazzles me with piercing brightness, almost painfully. This passage sounds like a cold daybreak, like a blizzard blowing through one’s bones. When it snows here in Denver, over a decade into my love for the Gawain-poet, I still like to say the snawe snitters ful snart. I feel the werbelande wynde. Even when you do not know the exact meaning, isn’t the language just wonderful and suggestive? Doesn’t it put you in mind of tangled, ancient roots emerging from the rich soil at the bottom of the magnificent, familiar tree of modern English?

Here is one gorgeous modern translation of those lines, by Simon Armitage:

Now night passes and New Year draws nere, drawing off darkness as our Deity decrees. But wild-looking weather was about in the world: clouds decanted their cold rain earthwards; the nithering north needled man’s very nature, creatures were scattered by the stinging sleet. Then a whip-cracking wind comes whistling between hills, driving snow into deepening drifts in the dales.

But if the relationship between myself and Middle English was translated into the awkward language of human commitment, it was the language that first attracted me, the poetry that came courting, and the ubiquitous love of God in these texts that proposed marriage at last.

I am a proud product of public schools up until my doctorate degree, and would not change that. However, I was completely surprised as a result of my secular education when I realized how necessary it was to think and talk about God while reading medieval literature. I was used to mildly avoiding the God parts in the things I read. But now, you couldn’t avoid Him. He was everywhere. Even in the farces and satires, He peeped around corners as stability and goodness itself.

I found it all riveting, glorious, mysterious. Once, a family member asked me if I regretted not doing theology as my undergraduate major and doctoral path. I naturally regret all the ways in which I am ignorant. But it was in the tightly woven delight of story, of even words themselves, not exposition, not questions, that I fell in love with the person of Jesus Christ all over again.

Narrative and form teach the character of God as powerfully as traditional theological writing. How delightful it was, how incarnational, that poetry and writing could talk as seriously about Christ as formal theology, but so differently. Christ’s parables teach differently than Paul’s letters, as Langland’s Piers Plowman shows us a different story than the Summa Theologiae. Both tell us essential things about who God is. These forms, in fact, do theology of their own. Poetry and narrative model the unfolding, lived, often unanswerable story of love.

Of course, not all medieval literature is truthful or insightful about God, or celebrates the life of virtue. But even so, because of their difference, their beliefs, and their strangeness, medieval people showed me new things about my own faith. Gawain, for instance, is never explicitly about faith or sanctification or Jesus. But the Gawain-poet tells a story of humanity that led me to a fuller understanding of creation and failure and human systems because of the different world of its context and assumptions. When I started to read authors like Julian of Norwich or William Langland a couple of years later in my doctoral program, I would tumble head-over-heels all over again.

How did you end up here? How did you end up curious about medieval literature, or the literature of the past? I’d love to know.

What I’ve been up to this month:

Writing odds & ends of things, in crooks & crannies of time. As of this week, all three kids are in regular schedules, so I am hoping to finally write a few essays I’ve been mulling over.

Renovaré featured an excerpt from my book, Jesus through Medieval Eyes: Beholding Christ with the Artists, Mystics, and Theologians of the Middle Ages on their website. Check it out if you’d like to read a taste before buying the book, which just came out in paperback this month! Buy yourself or a friend a copy at Barnes & Noble, Amazon, Thriftbooks, or best of all, through your local bookstore!

Relatedly, if you’ve read Jesus through Medieval Eyes, would you do me the favor of leaving a review on Amazon (or whatever platform you prefer)? As much as online review culture kind of stinks, it really helps out authors that you love to rate or review their books. Thank you to those who already have, and thank you in advance if you do ♥️

The Old Books with Grace podcast has returned for season five! Last week, I welcomed

on to chat about women writers in the tradition of the Catholic Imagination; next week Dr. Lynn Cohick and I talk about the OG theologian: Paul.

What I’ve been reading this month:

Nonfiction:

wrote a new book that I am starting this week… The Mystics Would Like a Word. Very excited.Fiction: I have been on an Elizabeth Goudge re-reading spree. The Dean’s Watch, The Scent of Water, and now, The Bird in the Tree.

Medieval/Medieval-adjacent: A book on Duns Scotus, preparing for an upcoming podcast episode. Eek.

Article: The rector of my grandparents’ church, Fr.

, sent me a Substack post of his on Christian freedom and excellence after reading last month’s Medievalish on the Olympics. I enjoyed reading his philosophical musing on the meaning of freedom in the work of Father Servais Pinckaers, O.P.!

A Prayer from the Past

Today’s prayer, from the great twentieth-century theologian, Howard Thurman (1899-1981), powerfully spoke to me. Dr. Thurman was a philosopher, author, civil rights leader, and mentor to Martin Luther King, Jr. I found it in the collection Conversations with God: Two Centuries of Prayers by African Americans (Amistad, 1994), edited by James Melvin Washington. Thurman composed this prayer in 1951.

My ego is like a fortress. I have built its walls stone by stone To hold out the invasion of the love of God. But I have stayed here long enough. There is light Over the barriers. O my God-- The darkness of my house forgive And overtake my soul. I relax the barriers. I abandon all that I think I am, All that I hope to be, All that I believe I possess. I let go of the past, I withdraw my grasping hand from the future, And in the great silence of this moment, I alertly rest my soul. As the sea gull lays in the wind current, So I lay myself into the spirit of God. My dearest human relationships, My most precious dreams, I surrender to His care. All that I have called my own I give back. All my favorite things Which I would withhold in my storehouse From his fearful tyranny, I let go. I give myself Unto Thee, O my God. Amen.

May it be so.

Peace for your September,

Grace

P.S. Medievalish is free, and I’d be delighted if you shared it with a friend!

Still a Trollope stan. If you haven’t yet, read him—begin with Barchester Towers. I began with The Eustace Diamonds, which is also a good starting place, but the Barsetshire Chronicles are his best in my opinion.

Your statement, "I naturally regret all the ways in which I am ignorant." struck me. If I could revisit segments of my undergraduate studies, I would continue with my more curious inner self and dive deeper into the English I took for fun, in my spare time. I might not have recovered from a course containing Medieval literature. But then, my focus was [in the Muppet voice of Sam the Eagle] "business"! I was unfailingly practical, with my sights set on a "business" job, marriage, and hopeful middle-class upward mobility. Now, as I comfortably approach retirement years, I'm deep into the things I passed over: theology and Medieval English literature, loving the journey and delving deeper into my faith!

Thank you for sharing the "backstory." I plan on sharing it with my college freshman as I encourage them to find their passion and then seek ways to use it in the service of the world.