Dear friend,

I have been knee-deep in the strange river of medieval bridal mysticism, that uncomfortable and wonderful tradition of reading the Song of Songs as an allegory of Christ’s profound love for his bride, the Soul. Strange reading for Lent, one might say! Via the horniest book of the Bible, the curious reader enters a universe of birds, rich fruits, shady oases, and breasts and necks and limbs.

If you’ve read my book, Jesus through Medieval Eyes, you’ve already encountered some versions of and main players in the representation of Jesus as a Lover. Someone I mention, but do not spend much time with—though I would have liked to—is St. Bernard of Clairvaux, whose positive pile of sermons on the Song of Songs was enormously influential in the late Middle Ages. Today, I want to share some pieces from his stunningly beautiful sermon 61 on the Song of Songs with you.1

If you start to read medieval literature, you cannot escape Bernard. He’s everywhere, his words popping up in literature for nuns, in The Canterbury Tales, and as himself in the Divine Comedy (in Paradiso, naturally). He was born around 1090 to Burgundian nobility—and basically never stopped stirring the pot wherever he went. When he entered the brand-new Cistercian Order, a reformed Benedictine order, thirty young Burgundian noblemen came along for the ride and professed vows alongside him. He was the third of seven children, and practically his entire family, even his widowed father, took monastic vows in his powerful wake. You can almost tangibly feel the force of his fire and brilliance as you read his writings, which circulated widely after he founded the new Cistercian abbey of Clairvaux and became its first abbot.

Bernard, a busy fellow, also constantly wrote letters, advised the rulers of Europe, especially the King of France, vigorously intervened in the papal schism of 1130, and ferociously feuded with other giant personalities of the twelfth-century, Peter Abelard and Eleanor of Aquitaine (he wiped the floor with Abelard, but wily Eleanor held her own by hightailing it out of France and marrying Henry II).2 He also, unfortunately, bent his great gifts to more unsavory medieval projects: spearheading the disastrous Second Crusade, and avidly persecuting heretics to their deaths in Southern France. To sum up Bernard: many good things, many bad things—like most of us, except he was more naturally gifted and therefore more potent.3

When I read St. Bernard, I find it difficult to square these more violent features with some of his sparkling, otherworldly, scripture-soaked sermons and treatises. He is perhaps the most beautiful and clear-sighted writer on the love of God in the later Middle Ages. His sermons and treatises foster a deep and tender contemplative spirituality oriented towards the all-encompassing love of Jesus.

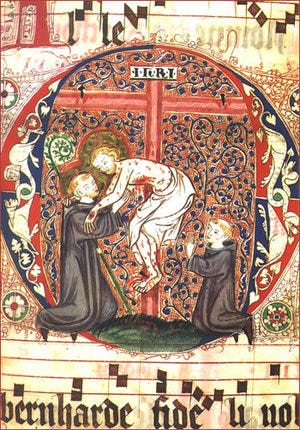

Sermon 61 on the Song of Songs is a masterpiece, especially as we travail through Lent and look forward to Easter. Bernard considers verse 2:14: “My dove in the clefts of the rock, in the hollow places of the wall, shew me thy face, let thy voice sound in my ears: for thy voice is sweet, and thy face comely.” In the classic medieval mode of reading scripture allegorically, with layer upon layer of meaning, Bernard connects this reference to both the wounds of Jesus on the Cross, which are a “cleft” of refuge for sinners, as well as Christ’s parable of the house built on rock in Matthew 7:24-29.

The wise man builds his house upon a rock because there he will fear the violence neither of storms nor of floods. […] And really where is the safe sure rest for the weak except in the Saviour’s wounds? There the security of my dwelling depends on the greatness of his saving power. The world rages, the body oppresses, the devil lays his snares: I do not fall because I am founded upon a rock. I have sinned gravely, my conscience is disturbed but not confounded, because I shall remember the wounds of the Lord. For ‘he was wounded for our transgressions’. What sin is so deadly as not to be forgiven in the death of Christ?”4

The love song of the bridegroom to the bride is a welcome into utter safety. Though the world is troubled, though we are tempted, though we even fall and destroy things ourselves, we can flee into the rock of the Body of Christ. Even as the fragile, fluttering doves hidden in the clefts of the rocks, there is nothing that can separate us from the love of God. I am reminded of the words of St. Catherine of Siena, advising Raymond of Capua: “Make your home in the wounds of Christ.”

What’s more, in a favorite trope of the Middle Ages, Christ’s wounds make the love of God readable, legible for us who would otherwise flee and hide in the face of our failures and weakness and fear. The nails that pierce him function like keys in a keyhole, “unlocking the sight” of the Lord’s will to love:

The nail cries out, the wound cries out that God is truly in Christ, reconciling the world to himself. ‘The iron pierced his soul’ and his heart has drawn near, so that he is no longer one who cannot sympathize with my weaknesses. The secret of his heart is laid open through the clefts of his body; that mighty mystery of loving is laid open, laid open too the tender mercies of our God, in which the morning sun from on high has risen upon us. Surely his heart is laid open in his wounds!5

As Christ’s body is laid open like a book opening up to his heart, we read the immeasurable will to love of God, that “mighty mystery of loving” on Good Friday. His pain is our pain. His weakness and mortality is ours. His heart for us is vulnerable, ready and open to receive us as we are. Christ on the Cross: refuge for sinners, friend to and literally one of the weak and brokenhearted, revealed heart for the world.

In some corners of the church today, I have seen a resistance to the bloody imagery that the medieval church so prized. Not too long ago I saw a tweet grousing about the dolorous hymn, “Nothing but the Blood of Jesus” and its too-close comparison to blood sacrifice and glorification of suffering. But such well-intentioned resistance ignores that we are embodied creatures of blood and guts, that we give birth in blood and water, that blood means life to us in our fragility and suffering. It is an act of sheer evil to crucify an innocent man, but nothing evil can end the far greater reality of Love as his character. His blood becomes witness to love, book of grace, invitation to mercy. In the wounds of Jesus, even as we deny Him, we witness, transformatively, truly, God with us, with us, with us.

Julian of Norwich follows Christ in one of her visions, as he beckons towards his opening side, into a fair country, “with enough room” for all. To paraphrase the eighteenth-century hymn by the wonderfully named Augustus Toplady: Rock of Ages, cleft for us! Let us hide in you.

What I’ve been up to this month:

I am currently in Houston (hello to all you Texans!), speaking at the Lanier Theological Library on art and women’s devotion to the side wound of Jesus. This beautiful, creative, challenging devotion has just lit me up this Lent—diving into this theme is making my head buzz with ideas, and filling me up with thankfulness and love for the devotion of my sisters of half a millennium ago, still teaching the gospel today.

I had the great pleasure of Zooming into a book club this month that had read Jesus through Medieval Eyes… what a joy to be together with this group from Phoenix from my basement in Denver. If your book club is reading or wants to read Jesus through Medieval Eyes, I’m always happy to jump in on a conversation and hear your thoughts and answer questions!

I finished a draft of a chapter on sloth & fortitude for my new book project… full of challenges and new/ancient perspectives… can’t wait to share it with you.

The Lent series of Old Books with Grace continues. In it, I have read penitential poems by Lady Mary Sidney Herbert, Countess of Pembroke, and Thomas Traherne. Tomorrow, a new episode comes out on John Donne. Listen on Apple, Spotify, or wherever you get your podcasts.

What I’ve been reading this month:

Fiction: It’s not very literary, but I’ve enjoyed Marie Benedict’s The Mitford Affair because the real life people in it are so wild. It’s about aristocratic English “bright young things,” the Mitford sisters, in the lead-up to WWII. Cousins to Winston Churchill, two were die-hard fascist friends of Hitler, another a communist who left without her parents’ knowledge to aid in the Spanish Civil War, and yet another a daring anti-fascist satirical novelist.

Nonfiction: Bryan Stevenson’s beautiful Just Mercy. Highly recommend.

Medieval/medieval-adjacent: I’m revisiting eminent medievalist Barbara Newman’s wide-ranging (but let’s be frank, wretchedly titled) From Virile Woman to WomanChrist, essays on gender in the Middle Ages.

Article: Sorry if this is cheating, but what an absolute treat for me to see Jesus through Medieval Eyes reviewed in Plough, my favorite journal.

Let me also put in a quick plug here: if you’ve read Jesus through Medieval Eyes, would you be willing to leave your honest review of it on Amazon? This not only helps others to find the book but affects the purchasing choices of book retailers (and it helps me out so much as a first-time author fighting the wiles of the algorithm)!

A Prayer from the Past

In honor of St. Patrick’s Day this week, I share an anonymous Gaelic invocation of Jesus. It is also a good one for spring. I am waiting for the renewal of the withered trees here in Denver for another month or so—eager for the green to come. Here it is, from Alexander Carmichael’s gorgeous nineteenth-century collection of oral Gaelic prayers and songs, Carmina Gadelica:

It were as easy for Jesu

To renew the withered tree

As to wither the new

Were it His will to do so.

Jesu! Jesu! Jesu!

Jesu! meet it were to praise Him.

There is no plant in the ground

But it is full of His virtue,

There is no form in the strand

But it is full of His blessing.

Jesu! Jesu! Jesu!

Jesu! meet it were to praise Him.

There is no life in the sea,

There is no creature in the revere,

There is naught in the firmament,

But proclaims His goodness.

Jesu! Jesu! Jesu!

Jesu! meet it were to praise Him.

There is no bird on the wing,

There is no star in the sky,

There is nothing beneath the sun,

But proclaims His goodness.

Jesu! Jesu! Jesu!

Jesu! meet it were to praise Him.

Amen.Peace for your March,

Grace

P.S. Medievalish is free, and I’d be delighted if you shared it with a friend!

If you have enjoyed this newsletter, you may also like upgrading to a paid subscription to receive other essays scattered throughout the month on medieval and early modern books and thinkers. Plus, you directly support my writing and podcast projects! In the last month for paid subscribers, I’ve done a countdown of my top five Do-Not-Miss Middle English Masterpieces, complete with recommended translations & resources for reading them…

Can you imagine your priest or pastor doing 61 sermons on Song of Songs—let alone EIGHTY-SIX, the final count?! Then, people like Gilbert of Hoyland thought it wasn’t enough because Bernard didn’t even make it through all the chapters of the Song of Songs, so Gilbert added a mere 47 more, also not completing the book. Finally, John of Ford added 120 and everyone thought that was probably sufficient—so much so that poor John’s works seem markedly less successful than Bernard’s and Gilbert’s.

I don’t know if this can be called a win in the end, as Henry II was a terrible husband who philandered and then basically locked Eleanor in a tower for sixteen years (for supporting a rebellion against him by their sons… not great either, but he forgave the sons and not Eleanor!).

At least, speaking for myself—maybe you’re a Bernard-level intellect gifted with towering leadership and spiritual insight, how should I know?

Bernard of Clairvaux, On the Song of Songs, Vol. III, trans. Killian Walsh OCSO & Irene M. Edmonds (Cistercian Publications, 1979), p. 143.

ibid.

In the evangelical church I grew up in, there was no space for wounded God. I remember the Pastor saying that Jesus defeated death and the cross which is why we shouldn’t portray him on the cross. The church was entrenched with prosperity gospel theology and struggled to face humanity’s own suffering in the world, let alone God’s.

It’s a shame because this perspective of God has more depth and is so much more comforting.

It reminds me of a quote by C.S. Lewis, “ If you look for truth, you may find comfort in the end; if you look for comfort you will not get either comfort or truth only soft soap and wishful thinking to begin, and in the end, despair.“

Profound! I loved reading and stewing on this!