Dear friend,

The last three weeks have been a clustercuss in Hamman world, to borrow a highly useful word from the excellent movie Fantastic Mr. Fox.1 Our household has gone through some deep and extended grief and anger, totaled a car, broken both the water heater and the kitchen sink within three days separately, and all, save me, succumbed to a weird flu for the last week. My writing has been minimal, and the bit that I’ve actually written is not my best. It feels strange to go into Lent excited, but I’m desperate for a change, for a new season with a sharpened focus even in the slogging mess of life these days.

I briefly mentioned Hugh of St-Victor (d. 1142) last month. He’s back for this month. Partially because I am still reading his Selected Spiritual Writings (my reading outside of light fiction tanked the last three weeks in all the big feelings) but also because I am delighting in his wisdom.

I can do no better than quote the midcentury British monk Aelred Squire to you: “In spite of the immense reputation which Hugh of St-Victor gained during his lifetime and has ever since enjoyed, the only biographical facts about him which it seems possible to place beyond all dispute are the day and year of his death.” Hugh himself was perhaps Saxon, or perhaps from around Ypres. He became part of the new community at St-Victor, close to Paris. It was a place steeped in intellectual and spiritual engagement. Hugh himself became an influential teacher, starting a flow of monastic thought and writing which would culminate, in his successors, in both the beginnings of systematic scholastic theology and in a mystical tradition of reading.

Hugh of St-Victor was a bit of an obsessive fellow. He wrote, as his translator notes, “three major spiritual works which are devoted to the theme of Noah’s Ark.” Yes, all three. The one I’ve been reading in these selections, De Arca Noe Morali, again the translator notes, “is translated here in its entirety except for a passage involving an abstruse geometrical argument.” These beginning sentences of the introduction sum up my interaction with Hugh well. My thoughts while reading him tend to bounce back and forth between two observations: Wow, he really dives deep into a theme in every possible way. What a beautiful passage. [two minutes later] Blargh, more Biblical numerology?

The patristic and medieval obsession with the numbers of the Bible has always felt like one of the stranger aspects of reading historical theology. They gloried in these scriptural numbers, spending pages getting to the bottom of them. A word from Hugh’s Didascalion clarifies why:

The foundation and basis of holy teaching is history, from which the truth of allegory is extracted like honey from the comb. If then, you are building, lay the foundation of history first; then by the typical sense put up a mental structure as a citadel of faith and finally, like a coat of the loveliest of colours, paint the building with the elegance of morality. In the history you have the deeds of God to wonder at, in allegory his mysteries to believe, in morality his perfection to imitate.2

For Hugh, not one jot nor tittle of scripture is without value to our lives right now. As Squire explains,

If the conviction is particularly prominent in the Didascalion that it is worth taking trouble even about things which may not seem in themselves worthwhile for the immediate purposes of the exegete, this is largely because the atmosphere of the work is dictated by concern for lectio divina, or holy reading…3

One starts with the things of time—the historical sense, what happened—and then you move into allegory, “the order of knowledge,” of digging deeper, of burrowing into the text and around it in every possible way. Even the numerical dimensions of the ark hold meaning.

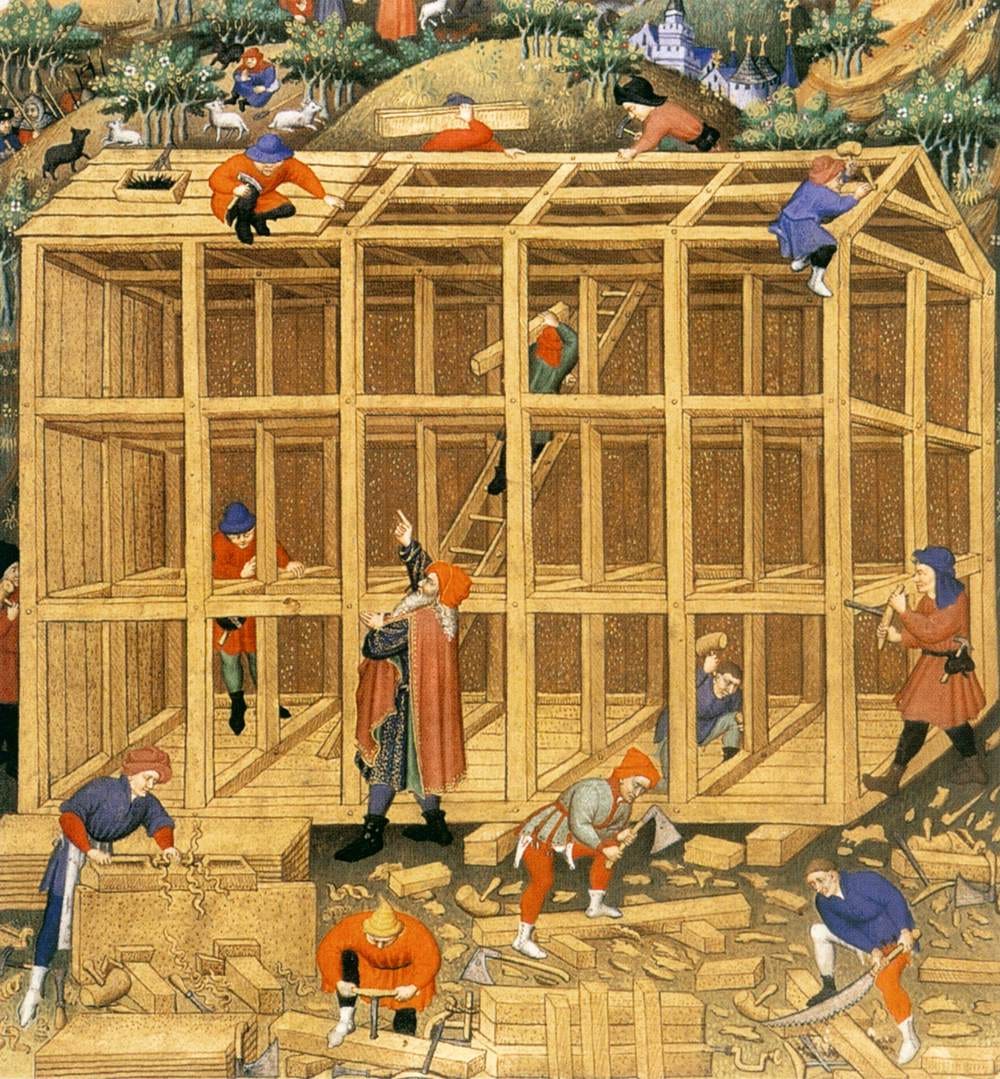

The passage I want to share with you today, however, thankfully refrains from the numbers obsession. Hugh has been thinking of building—of Noah building the ark, of Solomon building the temple, of Paul building the church. Hugh gently tells us that we, too, are builders. For the house of the Lord is the heart of every man and woman. The material for building, Hugh says, is our thoughts.

Let no one make excuse, let no one say: ‘I cannot build a house for the Lord, my slender means are not sufficient to meet such great demands. Exile and pilgrim as I am, and dwelling in a country not my own, I lack even a site. This is a work for kings… How should I build a house for the Lord?’ O man, why do you think like that? That is not what your Lord requires from you. He is not telling you to buy a piece of land from someone else in order to extend His courts. He wants to dwell in your heart—extend and enlarge that! Enlarge it, I say, for the Lord is great and cannot dwell in a strait space. Enlarge your heart, therefore, so that you may be able to contain Him whom the whole world cannot contain. … Where you yourself fail in doing this, He will enlarge it for you. A man whose heart had been thus enlarged by Him said to Him once, ‘I have run the way of Thy commandments, since Thou hast enlarged my heart.’4

This passage made me tear up when I first read it. Perhaps you are feeling, in this election year, in the burnout of ordinary life and struggles, your heart has become small and cramped. Perhaps you, like me, feel that your heart is no suitable place for Divinity in its unthinkable massiveness, in its unutterable glory, in its piercing goodness. I feel my exile keenly these days. I feel the self-imposed boundaries of my anxieties and petty hatreds and jealousies pulling curtains over the constricted soul space to make it more obscure.5

But here is the good news, from Hugh: the Lord does not want us to buy that land for him elsewhere, to look to others who feel better or holier or kinder or more serious. It is your own heart, being called into breathing space, into open air, into a fresh green country where it is good to dwell. This is the house of the Lord, and it is your own heart. This is what Hugh means, when he tells us to enlarge it. This enlarging may feel beyond your means, but if you ask for it, the Lord will do His work. Enlarging through becoming little is what He always does, and what He has promised.

There is no need, Hugh writes, to seek out thousands of craftsmen, to gather precious gems and marble, or to ship tall cedars from Lebanon across the ocean:

None of things is required of you. You will build a house for the Lord your God in and of yourself. He will be the craftsman, your heart the site, your thoughts the materials. Do not take fright because of your own lack of skill; He who requires this of you is a skillful builder, and he chooses others to be builders too… And in any case no one was wise who had not learnt from Him, and no one remained unskilled who was fortunate enough to be His pupil.

In other words, you are not called into fanciness or being extra, not even necessarily into the kinds of sainthood into which you see others called. This is your heart, with your mind, and your practices, and it is the Lord’s. Where are you being called into? What death, what shrinking are you being beckoned out of, into sunlight and art and hope and room? What walls must you knock down; what disciplines in throwing things away?

Does such a call leave you feeling inadequate and breathless and a little anxious? It does for me. But this is only a call into depth and love itself:

Call upon Him, therefore, beg and beseech Him, that He may deign to teach you too. Call upon Him, love Him; for to call upon Him is to love Him. Love Him, therefore, and He Himself will come to you and teach you, as He has promised those who love Him.6

Good news for the narrow-souled, that to call upon Him is to love Him.

So this Lent, whatever your practice looks like, remember that the underlying project is housebuilding and heart-enlarging. You are in the business of demolishing walls that impede the light, of repairing roofs that leak, of tossing the things you no longer need, of pulling the weeds, of setting the table for joy. If you have no energy, no knowledge, no building expertise, do not worry. As Hugh says, no one remains unskilled who is fortunate enough to be His pupil. And anyone who asks is His pupil.

What I’ve been up to this month:

Writing, poorly and with lots of feelings.

I had the pleasure of being interviewed on the The Habit podcast over at The Rabbit Room especially on habits of reading and writing, The Living Church on medieval ideas about Jesus, & the uproariously fun Faith Adjacent podcast on Jesus through Medieval Eyes.

The Lent series of Old Books with Grace starts on Ash Wednesday. I hope you all enjoy it—it’s right up the alley of subscribers to this newsletter, featuring the penitential poetry of four Early Modern poets, with a built-in time for reflection. Listen on Apple, Spotify, or wherever you get your podcasts.

What I’ve been reading this month:

Fiction: Laurus by Eugene Vodolazkin. Wow, so good. I should not have dragged my feet on reading this one.

Nonfiction: A classic work of midcentury literary criticism, The Seven Deadly Sins: An Introduction to the History of a Religious Concept, with Special Reference to Medieval English Literature, by Morton W. Bloomfield.

Medieval/medieval-adjacent: Handlyng Synne by Robert Mannyng of Brunne, a penitential treatise for both lay folk and learned set in poetry from the early fourteenth century.

Article: My friend

Bell over at Bell Farm wrote a beautiful piece for Comment on observing the kingfisher.

A Prayer from the Past

This prayer is by Paul Laurence Dunbar (1872-1906). Dunbar was an Black poet and novelist born to formerly enslaved parents in Ohio. One of the first African-American writers to achieve international fame, Dunbar wrote poems, essays, novels, and the lyrics to the first all-Black Broadway musical. He died of tuberculosis at thirty-three years old. It is from the collection Conversations with God: Two Centuries of Prayers by African Americans, ed. James Melvin Washington, Ph.D.

Lead gently, Lord, and slow,

For oh, my steps are weak,

And ever as I go,

Some soothing silence speak;

That I may turn my face

Through doubt's obscurity

Toward thine abiding-place,

E'en tho' I cannot see.

For lo, the way is dark;

Through mist and cloud I grope,

Save for that fitful spark,

The little flame of hope.

Lead gently, Lord, and slow,

For fear that I may fall;

I know not not where to go

Unless I hear thy call.

My fainting soul doth yearn

For thy green hills afar;

So let thy mercy burn--

My greater, guiding star!

Amen.Peace for your February,

Grace

P.S. Medievalish is free, and I’d be delighted if you shared it with a friend!

If you have enjoyed this newsletter, you may also like upgrading to a paid subscription to receive other essays scattered throughout the month on medieval and early modern books and thinkers. Plus, you directly support my writing and podcast projects! In the last month for paid subscribers, I’ve written about medieval nuns as artists, St. Augustine on charity, and have started a countdown of Do-Not-Miss Middle English Masterpieces…

I sometimes use that word in public and then realize I sound like a weird Puritan who doesn’t cuss if no one knows the reference… oh well, worth it.

Didascalion, vi, 3, quoted in Aelred Squire’s Introduction, p. 23.

Squire, Introduction, 23.

Hugh of St-Victor, Selected Spiritual Writings, translated by A Religious of C.S.M.V. (Harper & Row, 1962), De Arca Noe Morali, book IV, ch. 1.

Like Luke and Leia and Han in the trash compacter. Did not want to put in main paragraph, would really ruin the flow, but the Death Star trash compacter is sometimes my mental image of my heart.

Hugh of St-Victor, p. 123-124.

Oh how BEAUTIFUL is this? And timely. I'm so sorry you've been going through the ringer - I can relate. And your footnote about the trash compacter scene is spot-on and describes me well, haha!

Thank you for this. I've been wondering currently over my own role in what I can now name as soul building. It is one thing to denounce buying the land and gathering precious stone and metals to build, but it is another thing entirely to clear out the existing garden of the mind and build God's house in ones mind. It can be difficult to remember that all things material have immaterial beginnings; that faith is the evidence of hope and that that hope is for today.