Dear friend,

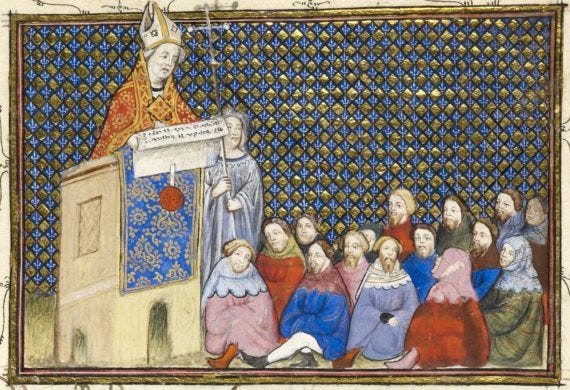

I’ve been reading some medieval sermons and guides for priests composing their sermons lately. I find medieval sermons both a little boring and a little fascinating. There are so few genres and public occasions today that we share with the people of the past, but one is the sermon, though of course it too was different back then. As a result, these sermons are often funny, reassuring and sometimes disturbing—humans have not changed too much.

For instance, people complained a lot about the sermons they heard. One visiting cleric notes of his sermon, hilariously, that

“I rede in holy write—I sey noght at I rede in Ouidie noyther in Oras; vor the last tyme that I was her, ich was blamyd of som men word, because that I began my sermon with a poysy.”

I preach from Holy Writ—I say nothing about what I read in Ovid or Horace; for the last time I was here, I was blamed by some men because I began my sermon with some poetry.1

No more secular poetry in sermons, please, said this man’s ardent critics. These listeners would certainly disapprove of the modern sermon format of the anecdote then scripture.

In stark contrast, some priests just added more and more poetry, in a classic medieval mode of embracing over-the-top. More is more. Like today, listeners generally had trouble paying attention, and priests were constantly employing questionable strategies to keep eyes and ears tuned in. In a sermon collection now called The Northern Homily Cycle, the priest has versified his entire repertoire of sermons for the liturgical year. The editor of this collection writes that

…the laity were often noisy and inattentive, complaining of boredom, and sometimes thronging outside in the courtyard where they would wait until the high point of the service, the moment when the host and chalice were elevated; they would then rush into the church to observe, leaving again afterwards as quickly as possible.2

Churches did not have pews until the Reformation era, so mobility was more normal. People sat on the floor or leaned against walls or moved around. (They even sometimes brought their hawks or dogs with them to church, much to the annoyance of their priests!) Verse is one way to capture wandering attentions and feet. And not all medieval sermons were snooze-fests. There are accounts of medieval people church-hopping, much as people sometimes do today, to listen to preachers who were especially good. In a world without easily accessible books or music, “poetry” from the pulpit was perhaps far more of a draw than we can fully understand. But I can’t help but think… can you imagine listening to someone preaching in bad verse for the entire liturgical year?! It also leads to sing-songy preaching like this:3

Seynt John the good Gospellere Seyth thus in oure Gospel here: A town was callid Capharnaum To whilk Christ was wont to com; A kingis sone ful sike ther lay, And when his fader the king herd say That Crist was comen to that cuntre That than was callid Galile... Saint John the good Gospeller Says thus in our gospel here A town was called Capernaum To which Christ was wont to come A ruler's son full sick there lay, And when his father the king heard talk That Christ had come to that country That was then called Galilee...

To be fair, it is an improvement on some sermons I’ve heard in my own lifetime. This style would almost certainly increase memory retention. More than anything, it reminds me of an especially thumping rhymed children’s Bible, but imagine verses and verses, weeks and weeks of this…

Like today, the quality of sermons was all over the place. Some Middle English sermons were unpardonably dull. Sometimes they were terrifying and gross. Very often they were horribly antisemitic. And sometimes they were beautiful and elusive—but I can’t tell, sometimes, if that’s just my own reaction to the ancient language, or how parishioners would have reacted as well back in the day. Often, though, they sprinkled in a verse or two amongst mostly prose. I liked this formula for effective preaching and reading scripture, from a manuscript now at the Bodleian:4

Primo, for to know thyng that is spedful. 2, for to echchew thyng that is synfull. Et 3, for to wytte thyng that is wondurfull. First, to know things that are helpful. 2, to avoid things that are sinful. And 3, to understand things that are wonderful.

I sometimes feel like sermons and bible readers skip the last part in favor of the “speedfull” and sinful. To see and know wonderful things. A good reminder. Here are a few wonderful things from Middle English sermons, for your enjoyment and meditation.

For the feast of the Ascension, we hear5

That the ʒate is open, The kyng is comen, The writte is broken, The sesyn is nomen. That the gate is open, The king is come The law is broken The season is appointed.

Don’t those lines feel almost Tolkienian? One can feel the growing joy and power in the anticipation of the coming kingdom.

How about this wise and memorable warning, on the vice of pride and its devastating power in community?6

the tonge brekith bone and hath hym-selue none. the tongue breaks bone, though it itself has none.

That’s certainly a sermon take-away that will stick with listeners.

But these lines, describing the character of St. John the Evangelist, are my favorite of what I’ve read recently.7

In herte clene and buxum, In speche mylde and louesem, In dede fre and gladsem. In heart clean and humble, In speech gentle and lovely, In deeds free and merry.

Now that’s an epitaph worth living out. I like those lines so much I might write them out and tape them above my desk.

Though I have been exploring Middle English sermons for ordinary parishes, there are some wonderful sermon collections from more famous folks given to their own flocks. They are far more sophisticated than these, which is sometimes good, and sometimes just different. Want some homilies from a woman? Try St. Hildegard of Bingen’s homilies on the gospels. How about from one of the most influential thinkers of the Middle Ages, St. Bernard of Clairvaux? You can read his sermons according to the proper season, which is a great delight. Sermons are often a great way to start reading theologians, and function as a gut check and fortifying shock to the system as one realizes how differently they read the Bible than we do, while (in my own experience, perhaps not yours) knowing it better.

What I’ve been up to this month:

Concerts, family birthdays, summer things! I’m a little sad to see the kids go back to school this next week.

Writing, writing, writing. Many people ask me how I find the time to write as a stay-at-home mom of three young kids over the summer. The answer is very early mornings. I’m soaking up these last mornings of summer before I lose morning work time and the scurrying, harried early mornings of school begin again for the eldest two!

I am delighted to share that professor & best-selling author

graciously wrote the foreword for my forthcoming book, Jesus through Medieval Eyes. I also received wonderful endorsements last month that I’m thrilled to share with you all. We are getting closer to October…

What I’ve been reading this month:

Fiction: Lest you mistakenly think I only read Serious Literary Things from the Past, I’ve been on an Emily Henry rampage (Beach Read, most recently).

Nonfiction: Oliver Darkshire’s Once Upon A Tome: The Misadventures of a Rare Bookseller. Fun.

Medieval/medieval-adjacent: Siegfried Wenzel’s edited & translated Summa virtutum de remediis anime.

Article: I came across this powerful James Baldwin op-ed on writing from 1962 in the NYT.

A Prayer from the Past

Today, I offer a prayer for the end of the day from my beloved Jane Austen, author of Pride and Prejudice and all her other wonderful books.

Father of Heaven, whose goodness has brought us in safety to the close of this day, dispose our hearts in fervent prayer. Another day is now gone, and added to those, for which we were before accountable. Teach us, Almighty Father, to consider this solemn truth, as we should do, that we may feel the importance of every day, and every hour as it passes,and earnestly strive to make a better use of what Thy goodness may yet bestow on us, than we have done of the time past. Give us grace to endeavor after a truly Christian spirit to seek to attain that temper of forbearance and patience of which the Blessed Savior has set us the highest example; and for which, while it prepares us for the spiritual happiness of the life to come, will secure to us the best enjoyment of what this world can give. Incline us, O God, to think humbly of ourselves, to be severe only in the examination of our own conduct, to consider our fellow-creatures with kindness, and to judge of all they say and do with that charity which we would desire from them ourselves. We thank Thee with all our hearts for every gracious dispensation, for all the blessings that have attended to our lives, for every hour of safety, health, and peace, of domestic comfort and innocent enjoyment. …Amen.

-Excerpted from Prayer III, from The Prayers of Jane Austen, ed. Terry Glaspey (Eugene, OR: Harvest House, 2015).

Peace for your August,

Grace

P.S. Medievalish is free, and I’d be delighted if you shared it with a friend!

If you have enjoyed this newsletter, you may also enjoy upgrading to a paid subscription to receive other essays scattered throughout the month on medieval and early modern books and thinkers. Plus, you directly support my writing and podcast projects! Lately for paid subscribers, I’ve written about a 17th-century plate found in a sewer, St. Bernard of Clairvaux, and a little medieval book of prayers and meditations…

D.M. Grisdale (ed.), Three Middle English Sermons from the Worcester Chapter Manuscript F.10 Leeds School of English Language. Texts and Monographs 5 (Leeds, 1939), 22.

The Northern Homily Cycle ed. Anne B. Thompson (Kalamazoo, MI: Medieval Institute Publications, 2008), 1. We know this because of the sermons preached against this kind of behavior.

Northern Homily Cycle, p. 190 (John 4:46-53)

MS. Bodl. 857 fol. 155r., found in Siegfried Wenzel, Verses in Sermons: Fasciculus Morum and its Middle English Poems (Cambridge, MA: Medieval Academy of America, 1978).

St Paul’s Cathedral, MS 8, fol 199r (p. 78 of Wenzel). Sesyn could also be a legal pun on session or seizing.

Wenzel again.

From a sermon from the Second Sunday of Advent, Wenzel, 200.

Oh I just loved all of this so much! It's always startling just how SIMILAR we are as humans through the ages ... These homilies (and the reactions) to them show this so well. Also interesting reminder how relatively new pews are! I always liked in Eastern Rite churches how mobile everyone is (so much easier with little ones). Maybe this is a lot more 'authentic ' to the early church than many might think. I'm definitely going to be putting that St. John epitaph on my mirror.

Oh! St. Bernard of Clairvaux's homilies by season?! I'm sold.