Medievalish 2.7

What does allegory do?

Medievalish hit 1000 subscribers this week! Thank you! I really appreciate all of you wonderful readers, and thank you especially for sharing this newsletter with your friends.

-Grace

Dear friend,

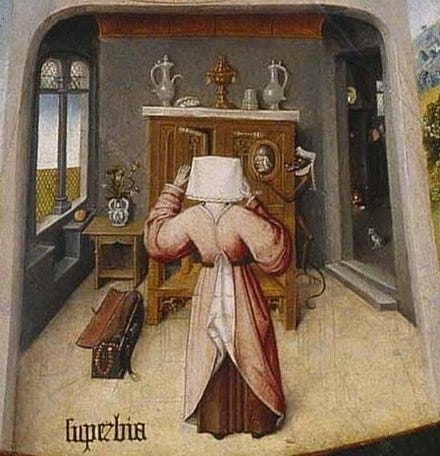

Today I want to think about a fraught topic: allegory (well, fraught for a rather limited, self-selecting audience—people who follow controversies about rhetorical devices). I’ve been reading a lot about the vices and virtues, which are regularly portrayed through allegory. Allegory, in case memories of your high school English class have been lost to the sands of time, is “a story, poem, or picture that can be interpreted to reveal a hidden meaning, typically a moral or political one.”1 It’s like a metaphor, but a complete narrative. It’s like a parable, but more complicated. It’s like a myth, but more straightforward, more one-to-one, in its hidden meaning.

As I started reading older literature, I was surprised by how much medieval and early modern Europeans adored allegory. They read scripture allegorically alongside reading it literally. Pick up any medieval commentary of the Song of Songs and you will drown in alternating beautiful and excruciating allegorical interpretations. They wrote wild, long allegorical poems like Piers Plowman and The Pilgrim’s Progress and Faerie Queene. They inscribed allegorical art onto the facades of cathedrals.

In comparison, allegory has really fallen out of favor in modernity. J.R.R. Tolkien was famously resistant to allegory, writing

I cordially dislike allegory in all its manifestations, and always have done so since I grew old and wary enough to detect its presence. I much prefer history – true or feigned– with its varied applicability to the thought and experience of readers. I think that many confuse applicability with allegory, but the one resides in the freedom of the reader, and the other in the purposed domination of the author.

-J.R.R. Tolkien, The Fellowship of the Ring

Is Tolkien right? Does allegory take away the “freedom of the reader” and place all power in the author’s pen?

It is true that allegory is much more wooden than myth and sometimes just silly. See this hilarious passage from C.S. Lewis’s The Allegory of Love, commenting on the extremely popular and influential Psychomachia by Prudentius:

I think that Tolkien, while right to resist readings of his own work as allegorical, sells that work of allegory short. The gift of allegory lies not in its flexibility or depth, but in its power to form readers. I do not mean in dominance. Allegory forms readers in attention to the meanings that lie under the literal. Before the complexity and multiplicity of myth or really good fiction comes the training of allegory into reaching for deeper meaning.

I have been idly musing on allegory ever since I realized the reason that Beauty and the Beast was my favorite Disney movie as a child. The initial draw was, obviously, that Belle had brown hair and liked books. But I think there was a second and deeper draw: underneath it all, I sensed the allegory at work. The Soul under the Spell of Selfishness is Led and Loved into Healing by Beauty. To paraphrase St. Paul, we were loved while we were still beastly. Spiritual transformation occurs only under the conditions of being loved, of being drawn by Beauty into beauty. I didn’t recognize it as allegory as a little girl, but I felt instinctively the pull into reflection and expansion of meaning.

In the sixth century, Pope Gregory the Great wrote of allegory as a sort of crane for our understanding:

For allegory supplies the soul separated far from God with a kind of mechanism by which it is raised to God . . . through means which are not alien to our way of understanding, that which is beyond our understanding can be known.2

Gregory was writing particularly of the passionate language of the Song of Songs, and of the power of the love of God which we can strangely receive through the language of human bodies and lovers. Our understanding begins with things we can grasp, dimly reaching towards ideas very difficult to express in ordinary, straightforward language.

Reading so many medieval allegorical texts has changed me as a reader. Take an initially unpromising example, a particularly stiff allegorical sequence in the fourteenth-century allegorical poem, Piers Plowman.

Ac ho-so wol wende ther Treuthe is, this is the way theder. Ye mote go thorw Mekenesse, alle men and wommen, Til ye come into Consience, yknow of god selue, ... And so goth forth by the brok, Beth-buxom-of-speche, Forto ye fynde a ford, Youre-faders-honoureth; Wadeth in at that water and wascheth yow well there... (C.VII.205-215) But who-so wishes to wend their way to Truth, this is the way: You must go through Humility, all men and women, Until you come into Conscience, known by God himself ... And come to the brook, Be-obedient-in-word, Until you find the ford, Honor-your-parents, Wade in there, at that water, and wash yourself well...

This allegorical map to the life of holiness drearily thumps on for quite some time, through the rest of the Ten Commandments and other virtues, through the gateways of penance, and so on. It’s all true enough—Humility does form a good Conscience. Part of the point is that this is allegory anyone can read. Beauty, with a capital B, means beauty, in Beauty and the Beast. Here, the gate Humility means humility. This reading beyond the literal is like riding a bike with training wheels. There are a lot of medieval texts like this, with very little to spice up the convoluted allegorical names, and not much insight to pull out of them. But the poet, William Langland, wrote its woodenness purposefully. It’s part of a sequence where the life of holiness seems close and easy. It seems like you’d simply be able to follow a map and end up living truthfully and virtuously.

Langland builds this kind of barebones allegory as a contrast to the rest of his poem. He writes the virtue Patience as both the very real virtue, and a critique of what happens when you sequester voluntary poverty from the complex whole of the life of human flourishing.3 Langland also writes a famous “confession” of the vices, with passages like this one:

Thenne cam Couetyse--Y can hym nat describe, So hungrily and holow sire Heruy hym lokede. He was bitelbrowed and baburlipped, with two blered eyes, And as a letherne pors lolled his chekes... (C.VI.196-199) Then came Avarice--I can't quite describe him, So hungrily and hollow Sir Harvey looked. He was beetlebrowed and large-lipped with two bleary eyes And his cheeks hung like a leather purse...

Avarice is a real fellow—Sir Harvey—and also so tied to the vice of avarice that his very face with its exaggerated features, brow jutting, prominent mouth opening, expresses his hungry, weary yearning for more. He has become the proverbial empty purse, his leathery cheeks hanging in hollow lack. Moreso, the allegory invites us into the character of avarice, the capital vice. The bejeweled glamor that avarice wraps itself within is gone. Avarice has become ravenousness, a unslakable desire to consume the world whole, a burning, hollow discontent with any good gift, disquietingly embodied as a person.

Langland’s allegories can simplify or expand, blow up or rebuild. And the reader must still do the work of it too, invited with a hand outstretched into continuing the interpretive work already begun by allegory’s naming.

Allegory is the handholding into interpretation beyond literalism. It’s like Hansel and Gretel’s white-pebbles into the wilderness of interpretation. It is hard to read myth or even “feigned history”—really good fiction—well, unless you have learned that literal reading is not all there is. In other words, we have to read allegorically before we can wade into myth.4 We learn how to read well, how to read body and soul together, neither one at the expense of the other. It is a long learning process (I originally had included an anecdote of my own process while reading Moby Dick in undergrad, and scrapped it because it all got too long… just know that once upon a time, I wrote a very embarrassing college essay about Ahab, Jesus, and allegory.)

Myth or fiction are more complex, more open to readers’ interpretation, and often more subtle and powerful than the sometimes clanking, rusty allegory. But like so many things that help us begin to learn something difficult, we then often think ourselves too sophisticated for it. Luckily, Langland really knocked that impulse out of me.

Allegory still has gifts to offer us. Culturally, we are at risk of reading more literally than ever, in a world of social media where immediacy of meaning is rewarded, in a world of AI where information is prized over mode and medium. I’m mulling over how reading (and writing?) allegory, even wooden allegory, can paradoxically help us reclaim some creativity and soulfulness in how we understand one another.

What I’ve been up to this month:

Kevin LaTorre, on his Substack, interviewed me about medieval poetry.

I’ve started doing magazine & podcast interviews for my forthcoming book, Jesus through Medieval Eyes: Beholding Christ with the Artists, Mystics, and Theologians of the Middle Ages. I cannot wait for October. Read about it and look at the beautiful cover in this earlier Medievalish post. It’s now available for preorder (Amazon, B&N, Christianbook.com where it is inexplicably cheaper, or check your favorite local bookstore)! Keep your eyes peeled—in not too long, Zondervan Reflective will be doing some special things with preorders…

I’ve changed up some things for the paid subscribers of Medievalish. Subscribe if you want to see more interesting posts about the medieval and medieval-adjacent things I’ve been reading and thinking about, or if you just would like to support this newsletter.

What I’ve been reading this month:

Fiction: I’ve been rereading some of George MacDonald’s novels. I just finished The Curate’s Awakening (original title: Thomas Wingfold, Curate). The covers of these reprinted works are so dreadful that I refuse to read them in public. But the content is wonderful. MacDonald was a 19th-century Scottish Presbyterian minister, one of C.S. Lewis’s favorite writers, and the hearty Scottish spirit in The Great Divorce.

Nonfiction: James K.A. Smith’s You Are What You Love.

Medieval/medieval-adjacent: So many Middle English penitential & pastoral materials. At the moment, the translation of the Somme le Roi in the manuscript British Library, MS Royal 18 A. X.

Article: Eleanor Parker’s musings on medieval stock phrases (or dare we say cliches?) in poetry, from History Today.

A Prayer from the Past

I sent you all a peek of a paid newsletter a couple of weeks ago, where I discussed the wonderful medieval devotional book, A Little Book of the Contemplation of Christ. In the 1577 edition of this book, this little rhymed prayer devotion is printed at the bottom of the pages, “three times in full, the fourth line with a difference at the end.”5 I wish we still did things like that in our printed books. Here it is for your own meditation. Imagine the first part of the line open on the lefthand page, and the second part on the right. (Remember that I=J and U=V!)

By Adams sinne Death did begyn. And by his fall We perish all. But Christ is iust. In him haue trust. And his iustice Makes thee rightwise. As you are, So were we. As we be, So shal ye. So discust, Dye thou must. But lyve for euer In Christ thy sauer. Fast and pray, Pitie the poore. Repent, amend, And sinne no more. Whilest thou hast breathe, Remember death. As grasse I passe From that I was. I hope agayne With Christ to raigne. Both ill and iust Death brings to dust. Yet none tell can The houre nor when. By faythe take hold. In Christ be bold. From canckered rust Christ shall make iust. God geueth all, Christ obtaineth all. The Holy Ghost Certifieth all. Fayth apprehendeth all, Works testifieth all.

Peace for your July,

Grace

P.S. As always, Medievalish is free, and I’d be delighted if you shared it with a friend!

If you have enjoyed this newsletter, you may also enjoy upgrading to a paid subscription to receive other essays scattered throughout the month on medieval and early modern books and thinkers. Plus, you directly support my writing and podcast projects! Next up for paid subscribers, a little bit on the fifteenth-century mystical writer and theologian, Nicholas of Cusa, as I read some of his selected spiritual writings…

According to Oxford Languages, maker of the Oxford English Dictionary.

Excerpted & translated in Denys Turner’s Eros and Allegory: Medieval Exegesis on the Song of Songs (Kalamazoo, MI: Cistercian, 1995), 217-218.

I wrote an essay on this back in grad school that is freshly out in a collected volume in honor of the great Julian of Norwich & Langland scholar (and one of my mentors!), Professor Denise Baker.

Lewis writes in Allegory of Love that the rise of allegory made room for myth in its diminution of the gods. He is arguing from a genre/writing perspective.

According to the translator, Sister Penelope Lawson (also known as A Religious of C.S.M.V.). This rhyme was printed on page 90 in her edition (London: A.R. Mowbray & Co. Limited, 1951).

Excellent thoughts on this, Grace! I agree with you when you say "I think that Tolkien, while right to resist readings of his own work as allegorical, sells that work of allegory short."

When you view allegory like you describe it as a stepping-stone to and method of training for more sophisticated and deeper things, I think you can appreciate it for what it is instead of looking down on it for what it isn't.

Almost laughed out loud at your comment about how dreadful the covers of George MacDonald's books are 😂 A few of them have been reprinted by Haleigh DeRocher with her artwork and they are gorgeous. I highly recommend!

But on a more serious note, I really enjoyed this piece. Since reading that Tolkien quote, I have been pondering how to view allegories. I love what you said about how allegories train us to look for deeper meaning. Thank you for sharing this!