Dear friend,

Happy Easter! On Good Friday, I kept my big kids home from school and we went to a service together at a local ministry, because our church’s service took place right at bedtime. Afterward, we walked the Stations of the Cross together, and very briefly talked about each one. But the highlight of the day was when we went together to look upon the big wooden cross set up for the service. No one was left in the room, just me and my three kids. And I knew what I wanted to do.

In the Middle Ages, there was a popular Good Friday tradition in parts of Europe. In England, it was called “creeping to the cross,” part of the long tradition of the Adoration of the Cross. Layfolk and clergy in a church would shuffle on their knees, or even crawl, to the cross to adore Christ in his suffering. It was especially popular on Good Friday, when the whole parish would creep to the cross together. Some churches today still follow a version of this practice.

William Langland mentions creeping to the cross in a wonderfully joyful sequence of poetry in the magnificent allegorical poem, Piers Plowman. Piers Plowman was written, rewritten, and rewritten again in Middle English in the fourteenth century. It’s long, confusing, and absolutely brilliant. It’s part of the medieval genre of poetry called dream visions, where a narrator falls asleep and then tells you their very often allegorical dream.

Wille, the personification of the human will, dreams of the cross and the Harrowing of Hell. Before the cross, the personifications called the daughters of God, Peace, Mercy, Truth, and Righteousness, had quarreled with one another on the right response to sin. Peace and Mercy had argued for clemency for humanity, while Truth and Righteousness had argued that humans needed to face the very real consequences of what they had wrought. In the Harrowing of Hell and the Resurrection, the sisters reconcile in the utter goodness of God, and Wille wakes up in ecstasy. I’ll quote at length, because it’s so lovely. Top is my loose translation, bottom is Middle English:

"After the sharpest showers," said Peace, "most shining is the sun; No weather is warmer than after watery clouds, Neither is love more precious, nor friends dearer, Than after war and wreck, when love and peace become masters. There was never a war in this world nor wickedest envy That Love when he wished, did not in the end bring to laughter, And Peace through patience all perils ended." "Truce!" said Truth, thou tells us truth, by Jesus!" Let us kiss to show our covenant, each of us to kiss the other." "And let no people," said Peace, "realize that we argued, For no thing is impossible to him that is almighty." "Thou says truth," said Righteousness, and reverently they kissed Peace, and Peace here, per secula seculorum [for ever and ever] ... Til the day dawned, these damsels caroled Then men rang to the resurrection, and right with that I awakened And called Kit my wife and Calote my daughter: "Arise and go reverence God's resurrection And creep to the cross on knees and kiss it as a jewel And the rightfullest of relics, none richer on Earth. For God's blessed body it bore for our benefit And it makes the fiend fear, for such is its might That no grisly ghost may glide where its shadow falls! "After sharpest shoures," quod Pees, "most shene is the sonne; Is no wedore warmore then aftur watri cloudes, Ne no loue leuore, ne no leuore frendes Then aftur werre and wrake when loue and pees been maistres. Was neuere werre in this world ne wikkedere enuye That Loue, and hym luste, to lauhynge ne brouhte, And peace thorw pacience all perelles stopede." "Trewes!" quod Treuthe, "thow tellest vs soeth, by Iesus! Cluppe we in couenant and vch of vs kusse othere." "And lat no peple," quod Pees, "parseyue that we chydde, For inposible is no thynge to hym that is almyhty." "Thowe saiste soeth," saide Rihtwisnesse, and reuerentlich here custe, Pees, and Pees here, per secula seculorum... Til the day dawed these demoyseles caroled That men rang to the resureccioun, and riht with that Y wakede And calde Kitte my wyf and Calote my douhter: "Arise and go reuerense godes resureccioun And crepe to the croes on knees and kusse it for a iewel And rihtfollokest a relyk, noon richore on erthe. For godes blessed body hit baer for oure bote And hit afereth the fende, for such is the myhte May no grisly goest glyde ther hit shaddeweth!" -William Langland, Piers Plowman (version C), XX.452-475

True resurrection joy and reconciliation! Langland paraphrases and expands Psalm 85, a favorite of the medieval church:

Mercy and truth are met together; Righteousness and peace have kissed each other. (KJV)

Justice and love, truth and mercy, are made lovingly and miraculously whole in the crucifixion and resurrection.

I’ve always loved Langland’s interpretation, and been fascinated by this idea of creeping to the Cross. It was often penitential in nature, an act of humbling oneself before the greatness of God’s goodness and his staggering humility and humiliation. Yet as Langland captures, it could also be joyful—for joy and humility are certainly not at odds with one another! True humility is real self-knowledge, the bone deep knowledge of who you are and what you are becoming in the dawning light of love.

Back to my three kids and I in the room, with the cross. I saw my chance, and I took it. I told my kids about this strange medieval tradition of creeping to the cross. We got down on all fours, and the four of us began to creep towards the big cross in the center of the room. The kids began to giggle. “Mama’s crawling like a baby!” called out the five-year old. Then the seven-year old exclaimed, with elation, “We are all Jesus’s babies!” And we all kissed the cross together.1

I teared up a little bit when she said that, and remembered the beautiful medieval metaphor of Jesus as our Mother, giving birth to his people in his labor-pains on the cross. In his resurrection, he raises us both from the dead and as a mother lovingly raises her children. My favorite medieval writer, Julian of Norwich, writes on this glorious similitude at length, if you haven’t encountered it before.

We are, indeed, Jesus’s babies. “Let the little children come to me,” says Jesus. And we crawl, in our littleness, eagerly, with joy or sorrow or frustration, to the Mother who loves us and labors for us always. In this labor, love and justice kiss, mercy and righteousness embrace.

What I’ve been up to this month:

An essay is in the mix that I hope to share with you soon!

Old Books with Grace finished up the Lent series, A Book that Changed Me. Take a listen on Apple, Spotify, or the platform you like best, to recent guests Kaitlyn Schiess and Claude Atcho discuss books that transformed their perspective—respectively, Madeleine L’Engle’s A Wrinkle in Time and Oscar Wilde’s A Picture of Dorian Gray. These episodes are available on your favorite podcasting platform, including Apple and Spotify. Even though it’s Eastertide now, you can still catch up!

Finished second revisions of Jesus Through Medieval Eyes. Publication date is Halloween!

What I’ve been reading this month:

Fiction: Susanna Clarke’s Piranesi. OH MY GOSH did I love it. Highly recommend. The most creative novel I’ve read in a long time. I can’t stop thinking about it.

Nonfiction: Alan Jacobs’ The Year of Our Lord 1943: Christian Humanism in an Age of Crisis. Focused upon the intertwining lives and concerns of Simone Weil, C.S. Lewis, W.H. Auden, Jacques Maritain, and T.S. Eliot. Jacobs’ style is incredibly readable, offering provocations to thought while remaining accessible.

Medieval/medieval-adjacent: A lovely, lovely little treatise by Hugh of St-Victor (c. 1096-1141) on divine love, translated by Sister Penelope Lawson. “O man, if you are still disposed to think it a small thing to have charity, listen; I tell you, God is charity. Is it a small thing to have God dwelling in oneself?”

Article: I really enjoyed this conversation between David Brooks and Luke Bretherton at Comment on Christian humanism. I didn’t mean to read so much about Christian humanism this month, but it kept serendipitously coming up. I happened upon it via another great article, from Matthew Milliner at Commonweal on Our Lady of Perpetual Help.

A Prayer from the Past

Lactantius (c. 250-c. 325), North African tutor to the son of Emperor Constantine, convert, and rhetor, wrote an Easter poem of the Earth celebrating the resurrection. This English version is from Fount of Heaven: Prayers of the Early Church, edited by Robert Elmer.

Lord, the bright stars show their joy, while the earth pours forth its spring gifts. …

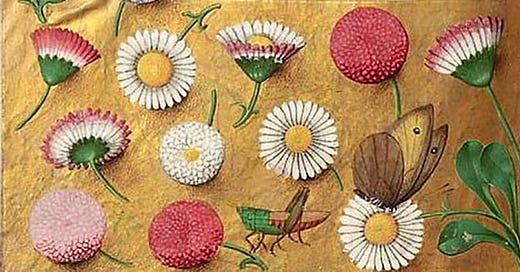

The bee, humming over the flowers, carries off honey. The bird, once sluggish with wintry cold, now returns to its song. The air sweetens with the melody.

The favor of the reviving world bears witness that all gifts have returned together with our Lord. For in honor of how you rose triumphant after your descent to the gloomy place of death, trees and flowers on every side show approval with leaves and flowers.

The light, the heavens, the fields, and the sea praise you, Lord. You crushed the laws of hell. You who were crucified reign as God over all things, and all created objects offer prayer to their creator.

We greet this festive day, to be reverenced throughout the world, the day you conquered hell, and gained the stars!

We applaud the changes of the months, the brightening light of days, the splendor of the hours. With their leaves the trees applaud in your honor. The vine, with its silent shoot, gives thanks. The thickets resound with the whisper of birds, and the sparrow sings with exuberant love.

Amen.

A bonus for pure Easter joy: a prayer-song that my heart sings for Easter is “Morning Has Broken,” the version by Yusuf / Cat Stevens. It’s older than fifty years, so it is a prayer from the past! Plus the original hymn was written by Eleanor Farjeon in 1931, and the tune itself is a very old Celtic folk melody, so it definitely counts.

Peace for your April,

Grace

P.S. As always, this newsletter is free, and I’d be delighted if you shared it with a friend!

Lest you mistakenly think we are a family with deep spiritual moments on holy days, note that we had a violent stomach bug on Easter and spent all of Easter eve and most of Easter itself in various positions of vomiting on one another. Less beautiful to write about for the newsletter, though equally embodied and relevant to being raised from the dead.

Love the Easter poem by Lactantius!