Dear friend,

The medieval era is unfairly maligned for many reasons. But in my opinion, there’s at least one thing that had a definite improvement in the so-called Renaissance: love poetry.

Medieval love poetry is usually either funny (intentionally or unintentionally) or horrid, or both: the ending of medieval bestseller Romance of the Rose makes me nauseous. Often it’s not really love poetry at all, at least not love poetry about the human beloved, but about something else: God or sex. The love poems to Christ are really wonderful, but I categorize them differently. I definitely think that human-to-human English love poetry gets much better after the fifteenth century—feel free to fight me in the comments.

John Donne’s “A Valediction Forbidding Mourning” (c. 1611) has been my favorite love poem ever since I first read it in my undergraduate years, in the Norton Anthology assigned textbook of a survey course that traversed a quick but glorious path from Beowulf to Paradise Lost.1 Donne’s poem is rather odd, for a love poem. It’s not about consummation, nor wooing, nor the beauty of the beloved. It’s an address to Donne’s beloved wife, as he is about to travel to the continent. He urges that they should not show the depth of their emotion as they part—a strange occasion for a love poem. Read it and see what you think:

"A Valediction Forbidding Mourning" As virtuous men pass mildly away, And whisper to their souls to go, Whilst some of their sad friends do say The breath goes now, and some say, No: So let us melt, and make no noise, No tear-floods, nor sigh-tempests move; 'Twere profanation of our joys To tell the laity our love. Moving of th' earth brings harms and fears, Men reckon what it did, and meant; But trepidation of the spheres, Though greater far, is innocent. Dull sublunary lovers' love (Whose soul is sense) cannot admit Absence, because it doth remove Those things which elemented it. But we by a love so much refined, That our selves know not what it is, Inter-assured of the mind, Care less, eyes, lips, and hands to miss. Our two souls therefore, which are one, Though I must go, endure not yet A breach, but an expansion, Like gold to airy thinness beat. If they be two, they are two so As stiff twin compasses are two; Thy soul, the fixed foot, makes no show To move, but doth, if the other do. And though it in the center sit, Yet when the other far doth roam, It leans and hearkens after it, And grows erect, as that comes home. Such wilt thou be to me, who must, Like th' other foot, obliquely run; Thy firmness makes my circle just, And makes me end where I begun.

The first few stanzas of the poem are very clever, but they are mostly clever and beautiful bragging about how special the relationship is between John and Anne. Other lovers are sublunary, mere layfolk uninitiated into the divine rites, sensible [sensual] rather than spiritual. But then we get into the stunningly strange and gorgeous metaphors of the final few stanzas, the metaphors for which Donne was so rightfully famous.

I first loved this poem because of these lines: “Though I must go, endure not yet / A breach but an expansion, / Like gold to airy thinness beat.” As one soul, the married lovers are not actually parted but expanded, their love a thin connective tissue from England to France—the thinness of beaten gold foil. When I moved to North Carolina from Arizona for my doctoral program, I thought of this image often in reference to the distance between my family and me. For though this image is meant to express the reality of marriage (and it does!) it also expresses the flexibility and reality of love across time and space. This gold is a different shape than the heavy gold of a ring or coin, which has its own density and weight in one’s hand. But it is gold nonetheless, gold turned flexible, thin and gleaming, spread over a greater space than one could have imagined, just as real and unified as the coin in one’s pocket or the ring on a finger.

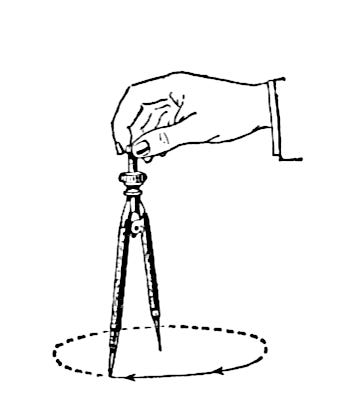

The second image that Donne takes up to describe the shape of their relationship is a compass. Not the compass of a ship’s captain, that points due North. It is a drawing compass, like this one, which lets you draw a perfect circle by hand, a notably difficult task:

If lovers are two, Donne writes, they are two as the feet of the compass are two: the fixed foot seems not to move, but subtly does as the other lover moves around it. The fixed foot leans yearningly towards the moving foot, and “grows erect” (we are never too far from erotic imagery in all of Donne’s poetry, religious or not) when the lover comes home.

Donne describes himself as the moving foot, and Anne as the fixed in this final stanza, which is my favorite. It draws out the beautiful implications in the image of marriage as a compass:

Such wilt thou be to me, who must, Like th' other foot, obliquely run; Thy firmness makes my circle just, And makes me end where I begun.

While John obliquely runs, that is, runs at a curious, bending angle, Anne is firm, in the Middle and Early Modern English sense of the word: stable, set, secure. The returning exploration of the one and the faithful steadfastness of the other together draw the perfect circle.

If we sit in this image for a moment, we discover layer upon layer of meaning. “Just” is part of a layered pun that invokes both the even roundness of a perfect geometric drawing and the justice we must learn to practice in our acts as humans, what we owe one another. Another meaning of “firm” is bound: Anne and John are bound together, and together they graciously lean into one another, one in movement and one steady. This “making circles just” is part of the calling of becoming a full human. One of the gifts of a good marriage or a true friendship is that it aids in the lifelong project of shaving off those corners and wobbly bits that hinder the justice of a true circle. A circle is also, as in its form of a wedding ring, a symbol of eternity, consummation, and completion.

Donne’s physical poetry nearly always ends up being metaphysical too. To “make me end where I begun” is a picture of faithfulness and steadfastness, a completion of the just circle. It reminds me of T.S. Eliot’s Four Quartets. In the magnificent “Little Gidding,” Eliot writes of the consummation of history:

We shall not cease from exploration And the end of all our exploring Will be to arrive where we started And know the place for the first time.

When the circle begins, you may not know it is a circle. You may be obliquely running on a path that feels far from where you began. It is only when you return that you know it for the shape it really is. You begin in grace; you end in grace.

I loved Donne’s poem before I got married, because it does not only speak to the condition of marriage, but to loving and being loved, knowing and being known. When I married, I recognized its truth again. But it’s not confined to married folk, it’s a universal calling into love—to lean into the invitation to let those to whom you are bound help you make your circle just when you are the one in oblique movement, or to aid others to make their circle just with your faithfulness, to end where you began, and to begin to know the place for the first time.

Happy Valentine’s Day!

What I’ve been up to this month:

My forthcoming book got a new title: Jesus Through Medieval Eyes: Beholding Christ with the Artists, Mystics, and Theologians of the Middle Ages… keep your eyes peeled for further updates as we get closer to October 2023! I alternate between extreme excitement and jittery nerves as the release date approaches…

On Old Books with Grace, I chatted with Julie Witmer, founder of the Elizabeth Goudge book club on Instagram, on our love for this under appreciated midcentury writer. Listen on Apple, Spotify, or any platform of your choice.

Getting back to some writing on art & the long tradition of the vices & virtues…

What I’ve been reading this month:

Fiction: I reread both George Eliot’s Silas Marner and Madeleine L’Engle’s A Wrinkle in Time for upcoming Old Books with Grace conversations in the Lent series, on transformative books. Both of them offer sheer delight and if you’ve never read them, you should. Stay tuned for their appearance in March!

Nonfiction: Howard Thurman’s Jesus and the Disinherited. I’m just starting this classic for the first time.

Medieval/medieval-adjacent: The glorious fourteenth-century alliterative poem Pearl, with the Medievalish Book Club, starting the poem this week. Upgrade to a paid subscription to receive access to these posts.

Article: I loved American Girl dolls as a kid. This article on Addy Walker, the first Black AG doll, was fascinating.

A Prayer from the Past

Our prayer today is a confessional prayer (that I’m going to pray during Lent!) from the 20th-century mystical British Catholic writer, Caryll Houselander. I found it in Elizabeth Goudge’s A Diary of Prayer:

We are the mediocre, we are the half givers, we are the half lovers, we are the savourless salt. Lord Jesus Christ, restore us now, to the primal splendor of first love. To the austere light of the breaking day. Let us hunger and thirst, let us burn in the flame. Break the hard crust of complacency. Quicken in us the sharp grace of desire.

Peace for your February,

Grace

P.S. As always, this newsletter is free, and I’d be delighted if you shared it with a friend!

Wow, must raise my love game, (to keep the Donne/Herrick pun going)! Fab meditation, Grace.

Thank you for this lovely reflection. I was not familiar with Donne's poem. It is beautiful!