Dear friend,

Composing this month’s newsletter did not come easy to me. I was feeling cranky about cold weather, knowing that there are still months of it—and the coldest, snowiest months, at that—to come. In the winter, my world shrinks as I am trapped in the house with small children. I feel dull; my creativity is drained by the cold darkness.1 Preparing to go outside in the snow with said children takes longer than the actual experience of being outside.

Feeling grumpy, I recited to myself the delightfully evocative descriptions of winter in the fourteenth-century Middle English alliterative masterpiece, Sir Gawain and the Green Knight to try to cheer myself up.

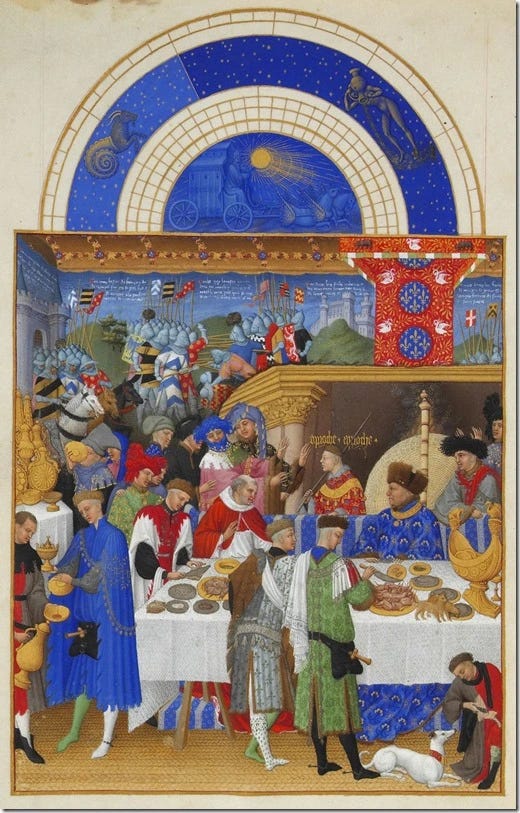

The poem opens with New Year’s gift-giving and feasting at the dazzling, glorious court of the young King Arthur. Fun side fact: For medieval folks, January first was not the beginning of a sober season of resolutions and trying to get back into shape and good habits from the excesses of Christmas. January first was the occasion for feasting and gift-giving far more than Christmas, as this beautiful illustrated calendar page for January out of the famous Tres Riche Heures du Duc de Berry shows us below.

Like the Duc’s court, the court of Arthur is glamorous, youthful, joyous, high on their own ideas of chivalry and prowess. Into this festive scene comes a giant knight, green from head to toe, upon a massive horse, who immediately insults Arthur’s honor. Gawain, the perfect young knight of King Arthur’s round table, enters into a game with the monstrous green man, where they promise to trade beheadings—and Gawain gets to behead the green man first. Unfortunately, rather than dying, the Green Knight gallops away. The disembodied head hanging from the headless knight’s fist proclaims that next New Year’s day, Gawain must come find him for Gawain’s own turn with the axe.

A year passes. Gawain prepares to go seek his likely end. The poet spends pages discussing Gawain’s immaculate armor and shield, which reflect the young knight’s commitment to God and identity as the perfect flower of chivalry. Gawain fights many monsters along the way, but the worst part is winter itself. The top is Middle English, the italics are from the great translation by Simon Armitage:

For werre wrathed him not so much that wynter nas wors, When the colde cler water fro the cloudez schadde And fres er hit falle myght to the fale erthe. Ner slayn wyth the slete he sleped in his yrnes Mo nyghtez than innoghe, in naked rokkez Thereas claterande fro the crest the colde borne rennez And henged heghe ouer his here in hard iisseikkles... The hasle and the hawthorne were harled al samen, With rough raged mosse rayled aywhere, With mony bryddez vnblythe vpon bare twyges, That pitously ther piped for pyne of the cold. And the wars were one thing, but winter was worse: clouds shed their cargo of crystallized rain which froze as it fell to the frost-glazed earth. Nearly slain by sleet he slept in his armor, bivouacked in the blackness among bare rocks where meltwater streamed from the snow-capped summits and high overhead hung chandeliers of ice... Hazel and hawthorn are interwoven, decked and draped in damp, shaggy moss, and bedraggled birds on bare, black branches Pipe pitifully into the piercing cold. (ll. 726-732; 744-747)

I have always related on a personal level to the “birds unblithe” peeping piteously on bare branches. Setting my own feelings aside, this is perhaps the most marvelous winter poetry in Middle English, filled with fantastic images: icicles, the cold water clattering and chattering over naked rocks, tangled, dead-looking plants, Gawain’s own ice-cold armor.

From the freezing landscape, Gawain prays to God and appeals to Mary. A castle, so beautiful and intricate that it might have been made out of paper, appears before his eyes. Relieved, Gawain enters—and faces deeper temptations than any in the wilderness that culminate in his second meeting with the Green Knight on New Year’s Day.

I won’t totally spoil the poem for you (can you spoil a 650-year-old poem?), but this castle is a place where Gawain’s pride in his prowess and confidence in his chivalric perfection will be shattered, through his own failures. It turns out to be another figuratively wintry place for Gawain, though it is cloaked in comfort. It’s quite striking that the answer to Gawain’s prayer in the icy wilderness is a place of impending failure for Gawain.

Failure, we eventually will realize, is a gift for Gawain: a knight chivalrous and moral, yet incapable of recognizing his own unseen ugliness, which emerges by the end of the poem. Gawain will replace the previous signs of his knightly perfection—his immaculate, stylish armor and his decorated shield—with a symbol of his failure and limitations.

Gawain and its various wintry challenges remind me of this prayer from 19th-century Presbyterian pastor and writer, George MacDonald. I found it in Elizabeth Goudge’s wonderful Diary of Prayer.

O Father, help us to know that the hiding of Thy face is wise love. Thy love is not fond, doting and reasonless. Thy bairns must often have the frosty cold side of the hill, and set down both their bare feet amongst the thorns: Thy love hath eyes, and in the meantime is looking on. Our pride must have winter weather.

MacDonald and the Gawain-poet share a conviction that failure itself is often God’s strange gift.

For MacDonald, winter is a season that invites hidden and quiet fortitude, and creaturely self-knowledge. It is chastening but not punitive. The secret grace of winter is that it gives that self-knowledge: humans are wonderfully embodied, created, limited. We are not the invincible gods that we sometimes feel we are in the glories of our summers, figurative or literal.

I want warmth and easy walks outside. I want learning and healing to be undemanding. But winter is the great slow-down that includes both rest and the wrestling of self-examination, unlike the manic and surprising growth of Spring, the energetic play of Summer, or the harvest busy-ness of fall. The seed lays dormant in the ground gathering strength; the bears and the snakes sleep to preserve energy. Other animals do as we do—wrestle in winter’s difficulties, then hunker down. Wintry weather, literal or metaphorical, is a stumbling place for pride’s driving desire to keep going, achieving, and the temptation to see myself as other than human. “Our pride must have winter weather.”

The season of difficulty and scarcity, struggling with snowsuits for five minutes of fresh air, frustration, piercing cold and sleepy darkness is also the season of slowing down (including feasting!) and tender, growing humility.

I’m still eagerly awaiting spring, though.

What I’ve been up to this month:

Recovering from the flu, feasting, traveling, not much writing accomplished!

Old Books with Grace returns January 25th with guest Dr. Anthony Domestico, professor of modernist poetry. We talk T.S. Eliot, my favorite modernist poet. Check it out on the podcasting platform of your choice in a couple of weeks!

Deciding what medieval thing the Medievalish Book Club should read after we finish Julian of Norwich next week. Join us by upgrading to a paid subscription.. I’m leaning towards Pearl, another of the Gawain-Poet’s poems… deciding what I should do for the Lent series on Old Books with Grace… decisions.

What I’ve been reading this month:

Fiction: I reread J.R.R. Tolkien’s Silmarillion for the first time in a decade or so. This was honestly such a fun Christmas break read, especially with the beautiful new illustrated edition I received as a gift.

Nonfiction: Madeleine L’Engle’s The Irrational Season. Thoughtful, contemplative, good start to the new year.

Medieval/medieval-adjacent: Roger Wieck’s Painted Prayers: The Book of Hours in Medieval and Renaissance Art. This accessible introduction with copious photographs really fed my burgeoning book of hours obsession.

Article: I do not usually share op-eds in this space, but Rowan Williams’ piece on the disaster of the “cost of living” crisis in The Guardian powerfully articulates what’s at stake for Christians as we think about economics and “covenantal” community (he writes from his English context, but his words are applicable globally).

A Prayer from the Past

This month, pray alongside Martin Luther King, Jr. in his own words in honor of his birthday. I found it on the Martin Luther King, Jr. Institute at Stanford University website, with some other prayers you might like to read and pray.

Most Gracious and all wise God; Before whose face the generations rise and fall; Thou in whom we live, and move, and have our being. We thank thee for all of thy good and gracious gifts, for life and for health; for food and for raiment; for the beauties of nature and the love of human nature. We come before thee painfully aware of our inadequacies and shortcomings. We realize that we stand surrounded with the mountains of love and we deliberately dwell in the valley of hate. We stand amid the forces of truth and deliberately lie; We are forever offered the high road and yet we choose to travel the low road. For these sins O God forgive. Break the spell of that which blinds our minds. Purify our hearts that we may see thee. O God in these turbulent day when fear and doubt are mounting high give us broad visions, penetrating eyes, and power of endurance. Help us to work with renewed vigor for a warless world, for a better distribution of wealth, and for a brotherhood that transcends race or color. In the name and spirit of Jesus we pray. Amen.

Peace for your January,

Grace

P.S. As always, this newsletter is free, and I’d be delighted if you shared it with a friend!

From this, you’d think I lived in the plains of Canada or something. I don’t. I live in the suburbs of Denver, which I know offers winter-lite for the true Northerners out there. But for this Phoenix native (winter is when you pick oranges in the backyard with a light sweater), Denver feels like endless wintry hell around mid-January.

I've read Gawain and the Green Knight twice now (Tolkien's translation). Glad you're considering Pearl for the book club. Such a beautiful poem!

Thanks for this. Just what I needed today, to consider how winter and failure can be “chastening but not punitive.”