Dear friend,

After my conversation on beauty with the wonderful Sarah Clarkson on Old Books with Grace a few weeks ago, I’ve been thinking a lot more about beauty. C.S. Lewis’s review of J.R.R. Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings rattles around in my mind: “Here are beauties which pierce like swords or burn like cold iron; here is a book that will break your heart.” He was right. In the theatre, before I had even read the book, I cried over the death of Boromir, because I was sad, but even more because it was beautiful: what Boromir had done for the hobbits, how he spoke to Aragorn in his end. When I did read the books, I cried again, multiple times—when Éowyn slays the Nazgul king, when the fellowship rests in Lothlórien, when the elves leave Middle-Earth. I am not usually a book crier, especially at the slightly callous age of thirteen. Why does beauty wound us at times?

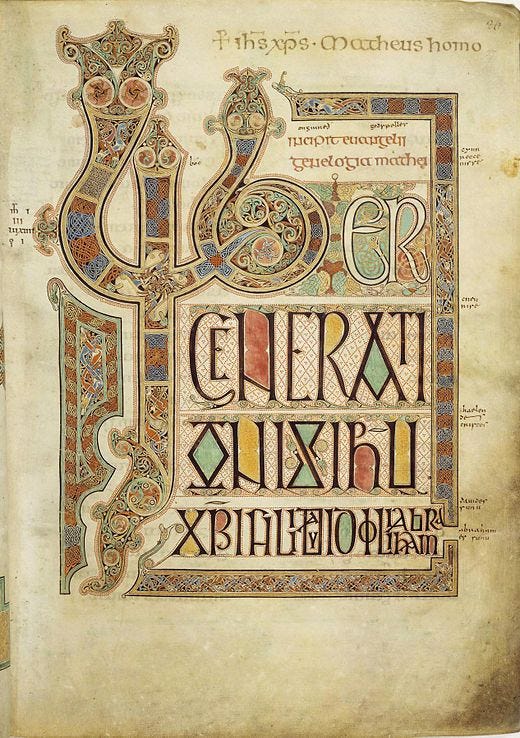

In college, I was visiting London before working at a youth camp in Italy. I had just taken a course on the history of the English language that had lit a small and curious fire within me. The cover of the course textbook featured the glorious Lindisfarne Gospels, crafted lovingly by Eadfrith, Bishop of Lindisfarne, around the year 700. I was not yet remotely imagining that I was going to get a doctorate in medieval literature.

I had persuaded my boyfriend (now husband of eleven years!) to accompany me to the British Library to see Jane Austen’s writing desk. Always up for an adventure, he agreed. He had probably not counted on coming around the corner in the British Library treasures room and seeing me suddenly dissolved in tears.

For I had come around that same corner moments before and suddenly, the Lindisfarne Gospels, gleaming in its display like a massive jewel, took up my vision. I knew what they were immediately; I did not know they would be at the library. They overpowered me. The “incipit” page of Matthew was open. The picture below cannot do it justice. Through teary eyes, remembering my English language class, I read the earliest surviving English gospel words, roughly, onginneth godspelle, [here] begins good news. In the best way possible, I was punched in the gut, pierced in the heart by my encounter with unexpected, overwhelming beauty.

I have been wondering why this is, that sometimes beauty provokes this painful but deeply truthful response.

For me, piercing beauty unsettles me and makes me yearn; it makes me both grateful for and unsatisfied with the things of the world. How could the ancient monk Eadfrith, with his homemade inks and quills, on the holy island of Lindisfarne capture it in the year 700? His work becomes art and window, vehicle and invitation to something troublingly, mysteriously bigger, truer, nobler, more glorious. Eadfrith’s Matthew gospel page wounds me because it makes me long for a land I have never visited, colors I have not seen, and will not ever be able to acquire and hoard up for myself in my present life.

Sometimes I conflate that land, those colors, that painful beauty with the past. Perhaps I can finally claim it for my own if I study enough, learn enough, dig deeper into those secrets, or try to replicate their wisdom in my own life. But such a beauty simply cannot be possessed. It belongs to another world. My desire for beauty remains a wound, sometimes wincingly painful, but strangely, a welcome wound, one without which my life would be more drab, bland, and inconsequential.

In this way, beauty is perilous, an idea that saturates Tolkien’s mythos. The elf-queen Galadriel warns Legolas to avoid the gulls, for if he hears their piercing ocean cry, he will never again be satisfied with the woods. Yet Legolas’s path goes to the Sea, and he takes it with bravery. His desire for the Undying Lands will not allow him to stay in peace in Middle Earth and what he has known and loved. He has been permanently altered. Gimli and Boromir are terrified to enter Galadriel’s realm, Lothlórien, and both, in a sense, were right to be frightened. No one leaves unscathed after encountering the beauty of Galadriel, which is its own kind of fearful power. And yet, no member of the Fellowship would ever relinquish or avoid their time in Lothlórien.

Understanding this wound of beauty, the woundingness of otherworldly beauty, is one of the main places the new Amazon series, The Rings of Power, has fallen short. The elves are too much like ordinary people. They are not frightening in the power of their beauty, nor wounded by the beauty that surrounds them and used to encompass them in the Undying Lands, in the curious tension of the world that Tolkien created. While Amazon certainly spent the big bucks on making the production look beautiful, it lacks the wounds of beauty that suffuse Peter Jackson’s trilogy and especially the original books. I have some theories on why but will spare you here. I will gladly dive deeper into my pop-culture commentary in the new Substack chat feature, which I am going to enable out of curiosity to see what happens.

What I’ve been up to this month:

Crafting next month’s Advent Old Books with Grace series. Start whetting your appetite for Advent-themed and incarnational poems by T.S. Eliot, George Herbert, Christina Rossetti, William Langland, and some anonymous liturgical poetry. I am excited to share these meditations with you. The first episode comes out November 30th.

The recent Old Books with Grace episodes: recently, I have welcomed Sarah Clarkson on beauty (as I mentioned above) and Robert Elmer, editor of several books on praying historical prayers written by the Christians of the past. Listen on Apple, Spotify, or the podcasting platform of your choice.

What I’ve been reading this month:

Fiction: I just read Elizabeth Goudge’s The Little White Horse for the first time. Delight and beauty. I’m going to read it to my oldest daughter over the holidays.

Nonfiction: James K.A. Smith’s Inhabiting Time: Understanding the Past, Facing the Future, Living Faithfully Now. I have been savoring this one slowly. Exploring time and our orientation as creatures in time, this book contains things I have thought but not known how to articulate for years. Highly recommend.

Medieval/medieval-adjacent: Julian of Norwich! Upgrade & join the Medievalish Book Club and read with me. You can read more about it here. I’ve been rewriting a lot of my old notes and I so deeply admire her mind and heart.

A Prayer from the Past

I have been challenged by the idea of these wounds, especially through medieval people, who are always far more ready to request wounds than I ever am. Writers like Julian of Norwich are captivated, even haunted by the idea that we worship a wounded God, whose pierced hands and feet are not healed even after resurrection.

I came across this beautiful anonymous medieval lyric prayer in Carleton Brown’s Religious Lyrics of the XVth Century, asking for the wound of love, which is so closely related to the wound of beauty. I have translated it on top, the bottom remains Middle English.

Jesus, my love, my joy, my rest, Thy perfect love close in my breast That I thee love & never rest; And make me love thee of all things best, And wound my heart in thy love free, That I may reign in joy evermore with thee. Ihu, my luf, my ioy, my reste, thi perfite luf close in my breste that I the luf & neuer reste; And mak me luf the of al thinge best, And wounde my hert in thi luf fre, that I may reyne in ioy euer-more with the. -From British Library Add. MS. 37049

Amen.

Peace for your November,

Grace

P.S. This newsletter, as always, is free, and I’d be delighted if you shared it with a friend!