Finding Books in Unexpected Places

I can’t believe it’s July already. That’s all I have to say about that.

For obvious reasons, I think a lot about reading. Something that I love about medieval people: they saw books everywhere. Everything was a potential book, a potential lesson or object of beauty or both, ready to be read. Actual books were rare and costly, but learning was out there for the taking.

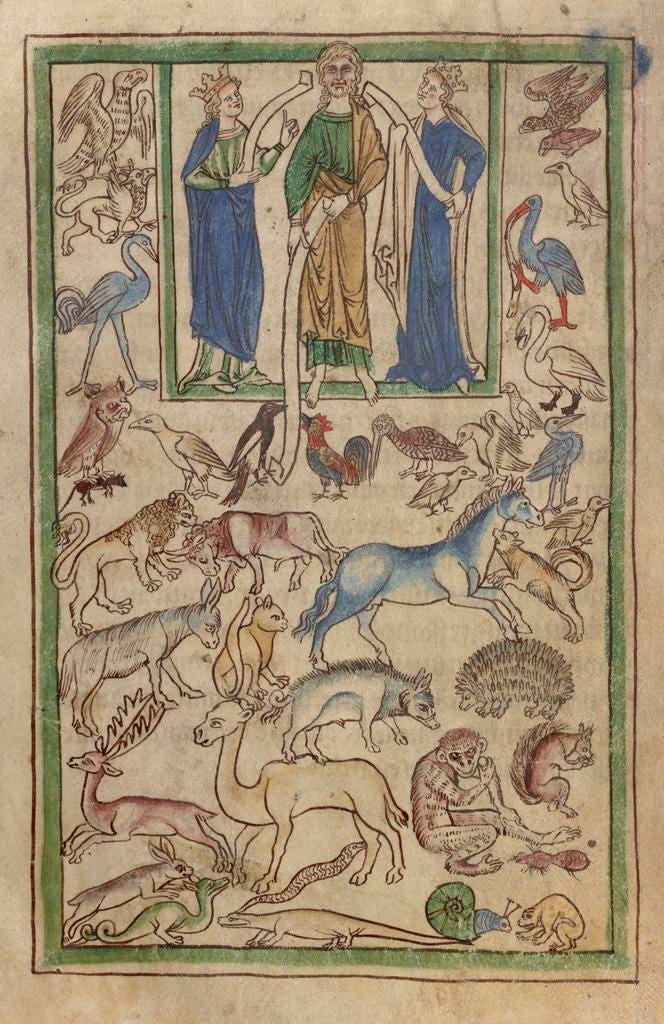

For instance, nature was a book of multitudes just waiting to be read. Bestiaries, those delightful catalogues of beasts, described how we might see the character of God, the devil, salvation, and ourselves in creatures, through blocks of text and outlandish manuscript illustrations of things as ordinary as pigeons and as wild as phoenixes.

A more somber book offered up for reading was Christ’s own body. Friar William Herebert (d. 1333), a lecturer for the Franciscan schools at the new-ish University of Oxford, wrote a beautiful little lyric poem to the Virgin, part of which I have excerpted and translated for you below:

Sithe he my robe tok Also ich finde in bok, He is to me ibounde; And helpe he wol, ich wot, For love the chartre wrot, The enke orn of his wounde. Since he my robe took As I find in book, He is to me bound; And help he will, I wot [know], For love the charter wrote, The ink ran from his wounds. -William Herebert, from Religious Lyrics of the XIVth Century, ed. Carleton Brown (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1952), p. 19.

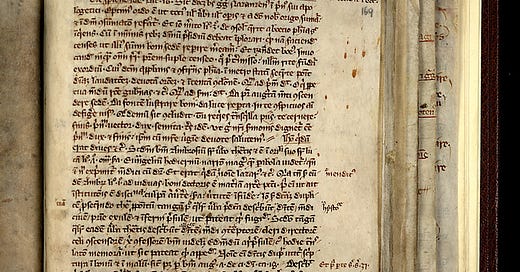

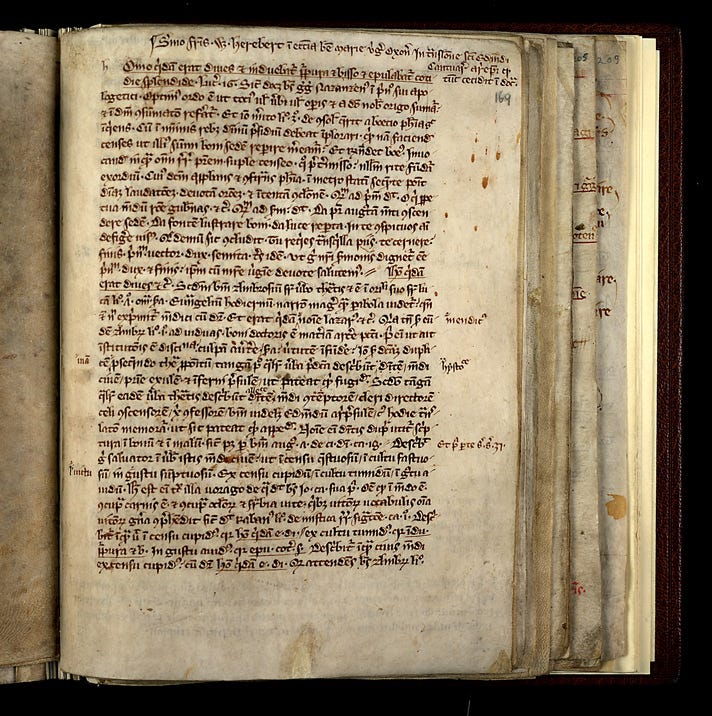

Herebert was one of many who pictured Christ’s body as a book of love, in his case, specifically a charter, a legal document granting rights or authority. This metaphor drew upon the process of bookmaking itself. Naturally, before the printing press, books were not made with paper, but with parchment, animal skin that had been scraped clean of hair or fur. Here’s a parchment page from Herebert’s commonplace book, one of his sermons written in his own beautiful, neat handwriting (!).

Pens were made from quills, sharpened and shaped, and they didn’t just leave gleaming ink on the surface of the page. They inscribed their meaning into the parchment itself, and careless scribes often punctured the page. This is why sometimes, even if the parchment was later scraped for some new purpose, we can faintly discern the writing once there. So medieval books were made of flesh, scraped, etched, “wounded” by words.

Herebert, with great tenderness, describes how Christ takes on our robe, garbs himself in our flesh. He is bound to us, bound with us, a motley collection of pages, becoming the great Book of Life in taking our nature. He writes salvation into himself on the cross, and his wounds spell out the meaning of the great charter of love.

Not that Herebert was necessarily thinking of it, but the “Magna Carta,” Great Charter, had been ratified about a hundred years before Herebert wrote this poem. This document granted certain rights and protections to King John’s noblemen and churchmen. John’s poor reputation has survived to the present day. He was forced to sign it and refused to abide by its terms. In contrast, this charter will not fail; “help he will, I know,” for this charter is written by love itself. In great medieval fashion, it is love, its endurance and total assurance, that we read in the ink that runs from the pen-scratched wounds of the Book of Life.

What I’ve been up to this month:

Season two of Old Books With Grace is concluded. I’m very, very thankful for all the wonderful guests who graciously agreed to come on a one-woman, basement-produced podcast, and especially for the gift of their conversations and wisdom. I would appreciate it if you left a rating or review on whichever podcasting platform you listen. If you’d like to support OBWG, you can buy me a “book” here to further my abilities to pay for web hosting, equipment, and the of course the books that go into making high-quality and interesting episodes.

I’m starting to prep for next season of Old Books With Grace. I love tinkering with it, figuring out the work-life balance and how many interviews to do, versus series that I write fully myself (like the Advent Carols series or the Lenten Virtues & Vices). I welcome feedback—do you enjoy series or interviews more? What kind of ratio do you like?

I have been working hard on the book project. Here’s something I didn't expect: every time I finish a chapter, it’s hard to get it out of my head. I learn to love each “face” of Jesus that I work on, and it’s surprisingly difficult to move on. Writing always offers unexpected gifts.

What I’ve been reading this month:

Nonfiction: Rowan Williams’ Christ the Heart of Creation.

Fiction: Light, fluffy beach reads. None have blown me away enough to recommend here, but I do love light reads when I’m wrestling with how to write about the Passion, phew.

Medieval/Medieval-adjacent: Recently devoured the delightful Poetry of the Passion, by J.A.W. Bennett, a medievalist and member of the Inklings alongside C.S. Lewis and J.R.R. Tolkien. Bennett traces themes in poetry centered on the crucifixion, from the Old English The Dream of the Rood to post-Reformation poets like Herbert and Crashaw. Academic, but fun to read in that midcentury criticism kind of way.

A Prayer from the Past

Our hearts can become books as well. The transcriber or author of this anonymous medieval poem-prayer has a little note of instruction to go with it: “In the saying of this orison, stop and abide at every cross and think on what you have said. For I have never found a more devout prayer of the passion!” (my translation, from Religious Lyrics of the XIVth Century, ed. Carleton Brown (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1952), p. 114). Excerpted from a longer poem, with my translation beneath:

Ihesu that hast me dere i-boght, Write thou ghostly in my thought, That I mow with devocion Thynke on thy dere passioun: For though my hert be hard as stone, Yet mayest thou gostly write ther-on With naill & with spere kene, And so shullen the lettres be sene. Jesus, that has me so dearly bought, Write thyself spiritually in my thought, That I might with devotion Think on thy dear passion: Even if my heart is hard as stone, You may still spiritually write thereon, With nail and with spear keen, So that the letters may be seen. ...Amen.

Peace for your July,

Grace

If you enjoyed this month’s Medievalish, I’d be honored if you shared it with a friend!